Student Populations

The student body is very diverse and beyond simple stereotypes or perceptions. Below are some resources on supporting students of different types, demographics, and needs.

Generation Z and Alpha Students

Generation Z students were born between 1995 and 2010. Generation Alpha students were born between 2010 and 2025. As noted in the HCC data presented earlier, these “traditional” age students coming to college straight out of high school are a minority of students at HCC. Nontraditional, older students also make up a significant percentage of enrollment.

Both Z and Alpha generations have grown up through significant challenges (such as pandemics and recessions), as well as significant technological and societal changes (such as smartphones, social media, high speed Internet, and AI). However, one should not assume students of these generations are necessarily more proficient in their technological skills. There is no such thing as “digital natives.” Technological proficiency is more correlated with socioeconomic status (SES, see below for resources on supporting low-SES students).

There are no characteristics that are inherent or innate to a particular generation, and even shared cultural circumstances are not experienced the same by all. Making assumptions about a student or a group of students based on age, gender, race, appearance, or other factors, is a bias we need to be cautious about. See a later section for resources on mitigating biases such as ageism.

Resources

- If You’re Z, Here’s What You See

- What Educators Need to Know about Generation Alpha

- Boomers and Generation Z on campus: Expectations, goals, and experiences

Dual Enrollment Students

Dual enrollment students complete HCC courses while still in high school. Often the courses are offered at the high school. This helps students get an early start on their college progress and eases the transition to college. A recent systematic review found that dual enrollment programs have positive effects on student success:

Using meta-analytic techniques, we find that across the 162 study effect sizes included in our analysis, participation in dual enrollment programs was positively associated with grade point average (GPA), total earned college credits, college enrollment, early persistence, degree attainment, and full-time attendance. Also, we find negative associations between dual enrollment and time to graduation and total semesters enrolled in college, indicating these programs can help students graduate college more quickly.

Below are some more resources on dual enrollment students.

- Twenty Percent of Community College Students Are in High School. Now What?

- Equity-Focused Possibilities for Dual Enrollment

- Dual Enrollment, Performance-Based Funding, and the Completion Agenda: An Analysis of Post-Secondary Credential Outcomes of Dual Enrollment Students by Credential Type

- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dual Enrollment Research

- Dual Enrollment Can Be Costly for Community Colleges

- A Guide to Early College and Dual Enrollment Programs

Nontraditional Students

Nontraditional students (sometimes referred to as ‘adult learners’) are typically 25 years or older. Many are coming from the workplace, and they may be more likely to have families, children, and other obligations. A significant portion of community college students are nontraditional. Nationally, approximately 40% of college students are nontraditional. Nontraditional students are retained at a lower rate than traditional students; however, a recent study found that adult student retention is boosted by engagement factors such as active and collaborative learning, student effort, academic challenge, student-faculty interaction, and support for learners. Here are some more resources about nontraditional, adult learners:

- Student Engagement and Retention of Adult Learners at Community Colleges

- Nontraditional Students: Supporting Changing Student Populations

- Demography Isn’t Destiny

- Association for Non-Traditional Students in Higher Education (ANTSHE)

First-generation Students

First-generation students are the first in their family to attend college. They may not have the family or social supports students often depend on to help acclimate and succeed in college. There is a “hidden curriculum” of unwritten rules and practices and expectations in college, for which some students may be unaware. A study looked at the difference between first-generation and continuing generation students:

First-generation college students (FGCSs) place more importance on achieving college-related goals and face greater difficulties from college- and other life-related challenges than continuing-generation college students (CGCSs).

These findings indicate that community colleges should offer more support to FGCSs pertaining to students’ goals and challenges so that all community college students may be successful in their academic pursuits.

There are numerous online resources and books on supporting the success of first-generation students, including:

- First-Generation College Students: Goals and Challenges of Community College

- Strategies for faculty

- Helping Faculty Help First-Gen Students

- Expectations of First-Generation Students and Continuing-Generation Students: How Faculty Can Make a Difference

- Academic Self-Regulation Interventions Can Promote Success for All

- “I’m Having a Little Struggle With This, Can You Help Me Out?”: Examining Impacts and Processes of a Social Capital Intervention for First-Generation College Students

- See more strategies in later sections such as inclusive teaching

- Help-seeking behaviors:

- “Just because I am first gen doesn’t mean I’m not asking for help”: A thematic analysis of first-generation college students’ academic help-seeking behaviors.

- A Qualitative Thematic Analysis of First-Generation College Students’ Help-Seeking Attitudes, Decisions, and Behaviors

- Examining active help-seeking behavior in first-generation college students

- Colleges need a deliberate online strategy to better serve first-generation students

- Center for First-generation Student Success – a NASPA initiative

- Books

Low SES Students

Low socioeconomic status (SES) students come from backgrounds and families with less income and economic support. Some students may even be homeless or have food insecurity. Low SES can make things more difficult or impossible, such as commuting to school, purchasing textbooks and supplies, accessing computers and the Internet, and paying tuition.

One study included anecdotal testimonies from low-SES students:

Talking to people, my teachers, building some sort of rapport with them I think is important and it means that I have some sort of connection level with the staff member and even if I’m not understanding I then feel comfortable enough to then go and approach and say hey what am I doing wrong here, can you help me?

For Anthony, making connections and developing relationships with academic staff was a key strategy utilised for success.

I am just wondering what are the common things that you see that high performing students do, and low performing students do and how can I be more like [high performing].

Something I found was I’d be talking to someone, just one of my student colleagues and I’d say something along the lines of, ‘oh you know I’m really struggling with maybe say referencing’ or something, and they’d say, ‘oh there’s actually a referencing sort of help section if you just go here’, and they’d send me like a link or something.

The amount that I learnt through YouTube videos as opposed to through [university name] on how to do certain tasks in order to then be able to do my assignments more effectively was unbelievable.

More resources on supporting the success of low-SES students:

- Addressing Social Conditions to Support Student Success: A Community College Imperative

- Tailoring Programs to Best Support Low-Income, First-Generation, and Racially Minoritized College Student Success

- An ecological approach to creating validating support for low-income, racially minoritized, and first-generation college students

- Successful university students from low socio-economic backgrounds’ perspectives on their academic success: a capital-based approach

- Advancing Equity and Opportunities for STEM Students From Low-Income Backgrounds: Evaluating the Impact of a Collaborative Support Program on Academic Outcomes

- “Success Is Not Measured Through Wealth”: Expanding Visions of Success for Low-Income STEM Students

Food Insecurity

In an article titled “Student Hunger: How We Got Here and Solutions to Increase Persistence” in New Directions for Community Colleges, the nonprofit organization Swipe Out Hunger found that:

- Approximately one-third of students report experiencing food insecurity.

- Food-insecure students have 42% lower odds of graduating.

- SNAP eligibility requirements currently exclude many students.

Another report found that “Overall, 23% of undergraduates, and 12% of graduate students, are experiencing food insecurity. This means more than 4 million students are food insecure.”

More Resources:

- Prevalence of Food Insecurity in a Community College District: Relationship Between Food Security and Grade Point Average

- Campus-based Interventions and Strategies to Address College Students with Food Insecurity: A Systematic Review

Student Parents

Student parents are juggling college, raising a family, and often a job, as well. Some may be single parents without the support of a spouse or possibly other family support, as well as facing more economic and time and mental health pressures than other students. Below are some resources on supporting student parents.

- The Family Friendly Campus Toolkit

- Raising Up is a docuseries which follows four student parents and their families as they juggle academics, childcare and work

- Multiple Responsibilities, Single Mission: Understanding the Experiences of Community College Parenting Students

- New supports help single moms at community colleges

- ‘Yes, You Belong Here’: An Expert Explains the Importance of Supporting Student Parents

- “I Had to Figure It Out”: A Case Study of How Community College Student Parents of Color Navigate College and Careers

- Like a Juggler: The Experiences of Racially Minoritized Student Parents in a California Community College Background and Context

- Mental health is a big, important issue for student parents

- College students who are parents face wide affordability gap, study finds

- Long before coronavirus, student parents struggled with hunger, homelessness

- Largely unseen and unsupported, huge numbers of student fathers are quitting college

Student Veterans

Student veterans actively serve in the military or served in the past. They may or may not be combat veterans. It’s important not to stereotype or lump student veterans into one category, as one report notes:

Student veterans are not who most faculty members, administrators, and other students think they are. For more than a decade, the image of the typical student veteran was shaped by the public image of combatants returning from Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom, more commonly known as the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively. In our conversations, campus leaders said that one of the most pervasive and pernicious stereotypes that campus stakeholders have about student veterans is that they all suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD continues to loom large in the American imagination as it is both a very real consequence of military service for some veterans and also an all-too-easy stereotype about anyone with military experience.

Some resources on supporting student veterans include:

- Student Veterans’ Perspectives of Higher Education Contexts: Beyond the Non-traditional Student

- The Importance of Student Veteran Belonging

- Best Practices at the Institutional Level: Enrolling and Supporting Student Veterans

- Veteran Ally: Practical Strategies for Closing the Military-Civilian Gap on Campus

- Student Veterans of America

Students with Disabilities

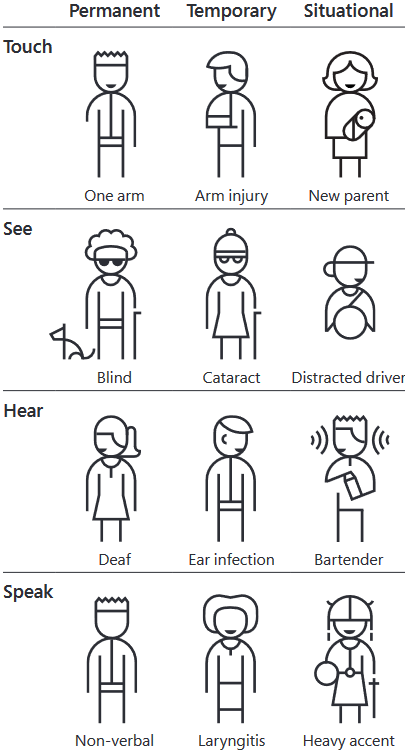

Students may have permanent, temporary, or situational disabilities that are visual, auditory, motor, or cognitive in nature, as illustrated in the diagram below from Microsoft Inclusive Design:

Thus, not all students who need support or accommodations may have permanent and declared disabilities. Some disabilities are invisible, including cognitive (neurodivergent) disabilities such as ADHD and autism. Such students often suffer from a stigma against disabilities. Some estimates suggest over 40% of people may have permanent, temporary, or situational disabilities. One should not also look on students with disabilities with a “deficit lens”, as students who are lesser than and need to be fixed. Instead, one can adopt an “asset lens” and explore the strengths of these students, in line with a more social model of disability:

The social model of disability identifies systemic barriers, derogatory attitudes, and social exclusion (intentional or inadvertent), which make it difficult or impossible for disabled people to attain their valued functionings. The social model of disability diverges from the dominant medical model of disability, which is a functional analysis of the body as a machine to be fixed in order to conform with normative values.

According to the Universal Design for Learning framework, revising our teaching to be more inclusive and accommodating to student differences can benefit all students, not just those with disabilities. Some example accommodating strategies include:

- Ensuring all your videos have accurate captions and all your images have accurate descriptions (“alt text”).

- Being flexible in your due dates, giving students second chances to complete their work.

- Sharing your lecture notes or slides, and letting students take notes using laptops or other devices if need be.

- Sharing lecture recordings or letting students record lectures, especially for students for whom English is a second language or who have cognitive or auditory impairments.

- Reducing or removing the use of timed exams and quizzes, or at least offering extended time for students who request it.

- Making attendance more flexible.

Some articles and resources on supporting students with disabilities include:

- Fast Facts: Students with Disabilities

- When ‘Rigor’ Targets Disabled Students

- Redefining Disabilities: Moving beyond the language of deficits and deficiencies and finding strength in difference

- 4 barriers to accommodation for students with disabilities

- How to Teach Your (Many) Neurodivergent Students

- Flipping the Script on Teaching Neurodivergent Students — and the Implications for All Learners

- Learning impacts reported by students living with learning challenges/disability

- Supporting the development of students with disabilities in higher education: access, stigma, identity, and power

- How Time-Management and Other Tools Can Help Students With Mental Illnesses Stay Enrolled

- “Mathematics is a battle, but I’ve learned to survive”: becoming a disabled student in university mathematics

- Perspectives from Undergraduate Life Sciences Faculty: Are We Equipped to Effectively Accommodate Students With Disabilities in Our Classrooms?

- Making Science Labs Accessible to Students with Disabilities

- Teaching Statistics to Struggling Students: Lessons Learned from Students with LD, ADHD, and Autism

- An Instrument to Assess Faculty Who Support Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder at Community Colleges

- Inside and Out: Factors That Support and Hinder the Self-Advocacy of Undergraduates with ADHD and/or Specific Learning Disabilities in STEM

- Top 20 Principles for Students with Disabilities

- National Center for Learning Disabilities

See the sections below on mitigating bias, accessibility, and inclusive teaching for more resources on supporting students with disabilities.

Latino Students

HCC is a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI). HSIs are colleges and universities that enroll at least 25% Hispanic students and receive federal grants to support their education and stability.

What is the difference between Hispanic, Latino, Latina, and Latinx? According to a resource from Duke University Medical School:

Hispanic refers to a person with ancestry from a country whose primary language is Spanish.

Latino and its variations refer to a person with origins from anywhere in Latin America (Mexico, South and Central America) and the Caribbean.

What about Latino, Latina, and Latinx? What do those endings mean?

These words are all gendered forms of the same word. Spanish is a gendered language, which means all nouns have either a feminine or masculine form. Feminine-associated words typically end in “a”, while masculine-associated words typically end in “o.” Spanish has no gender-neutral nouns or pronouns (like our “they” or “it”), so all nouns have to end in one of these forms.

The term “Latinx” attempts to correct this problem by offering a gender-neutral version of the term that does not end in “o” or “a.” However, this alternative creates some problems of its own. To start, words don’t naturally end in an “x” sound in Spanish, making the word sound awkward when spoken. Additionally, some members of the Latino community feel this term has been imposed on them by an English-speaking, mostly academic audience.

Here are some resources on supporting the success of Latino students:

- Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

- First-Year College Achievement and Graduation Rates for Hispanic and Hispanic First-Generation Students

- Risk Factors and Effectiveness of Implemented Academic Interventions on Student Retention at a Hispanic-Serving Institution

- Addressing equity gaps for Latino college students

- Motivation for Staying in College: Differences Between LEP (Limited English Proficiency) and Non-LEP Hispanic Community College Students

- Answering the Call for Title V Data: A Success Skills Intervention to Increase Retention at a Hispanic-Serving Institution

- Latino men and men of color programs: Research-based recommendations for community college practitioners

- A Socio-Ecological Outcome Investigation of the Student Engagement, Achievement, and Satisfaction of Latino Men in Community College Developmental Mathematics

- Rural Black and Latinx Students: Engaging Community Cultural Wealth in Higher Education

Black and Minoritized Students

Black students, students of color, and students from other underrepresented and minoritized demographics (such as Latino, Native American/indigenous, Pacific Islander, multiracial, and Asian and Asian-American) have unique challenges when participating in college.

Inclusive teaching practices (see later section with more details) can support these students and reduce equity gaps, as noted in this study:

First, a class where conceptual issues were studied before doing any complicated calculations had zero final exam grade gap between students from underrepresented racial or ethnic groups and their peers. Next, four classes that offered students a retake exam each week between the regular bi-weekly exams during the term had zero gender gap in course grades.

Below are some resources on supporting the success of these students.

- Toward Ending the Monolithic View of “Underrepresented Students”: Why Higher Education Must Account for Racial, Ethnic, and Economic Variations in Barriers to Equity

- The State of Black Students at Community Colleges

- Racism, sexism and disconnection: contrasting experiences of Black women in STEM before and after transfer from community college

- Black students are less likely to attain college degrees because of discrimination and external responsibilities, study finds

- Grade Gaps Reflect Course Problems, Not Students’ Shortcomings

- Perceptions of Discrimination Predict Retention of College Students of Color: Connections with School Belonging and Ethnic Identity

- Do introductory courses disproportionately drive minoritized students out of STEM pathways?

- The Role of Minoritized Student Representation in Promoting Achievement and Equity Within College STEM Courses – summarized in: Diverse College Classrooms Linked to Better STEM Learning Outcomes for All Students

- Where and with whom does a brief social-belonging intervention promote progress in college?

- Wise Critiques Help Students Succeed

- The Impact of Peer-Mentoring on the Academic Success of Underrepresented College Students

- My Professor Cares: Experimental Evidence on the Role of Faculty Engagement

See the section below on Male Students for some resources specifically about supporting the success of black male students.

LGBTQ+ Students

According to the Equity Evaluation Tool, LGBTQIA2S+ is an “acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, two-spirit (used particularly by Indigenous communities), and more. Sometimes, when the Q is seen at the end of LGBT, it can also mean questioning. LGBT and/or GLBT are also often used. The term “gay community” should be avoided, as it does not accurately reflect the diversity of the community. Rather, LGBTQ+ community is preferred (Achieving the Dream, 2022).”

According to the LGBTQ Students in Higher Education factsheet, 17% of undergraduate and graduate students identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual, asexual, queer, or questioning. 1.7% of undergraduate and graduate students identified their gender as transgender, nonbinary, or questioning.

“5 Ways to Become a Skilled LGBTQ+ Advocate” shares some tips for being an ally and advocate for LGBTQ+ students and all people, including:

Regardless of whether someone is part of the LGBTQ+ communities or not, asking everyone how they would like to be addressed and how to pronounce their name is a great way to make everyone feel included and respected. This also takes the awkwardness out of singling someone out and having to ask them for this information directly.

According to the journal Science:

It is important to recognize the context-dependent and multidimensional nature of sex. Rather than privilege any characteristic as the sole determinant of sex, “male” and “female” should be treated as context-dependent categories with flexible associations to multiple variables….No one trait determines whether a person is male or female, and no person’s sex can be meaningfully prescribed by any single variable.

Awareness of the distinction between sex and gender is another vital element to inclusive, quality research. Conflating the two harms and invalidates gender minorities by implying that these distinct attributes are inextricably linked.

Below are some further readings and resources:

- 5 Ways to Become a Skilled LGBTQ+ Advocate

- Better Allies – Everyday actions to create inclusive, engaging workplaces. See their free newsletter.

- Equity Evaluation Tool – designed for educators striving to create more validating and affirming learning experiences and environments for students who are Black, Latino, Indigenous, poverty-affected, first-generation, non-male-identifying, LGBTQIA+, and/or disabled

- Factors Influencing Retention of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Students in Undergraduate STEM Majors

- The Impact of anti-LGBTQ+ Legislation on U.S. College and University Students

- Intersecting the Academic Gender Gap: The Education of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual America

- Faculty perceptions of chosen name policies and non-binary pronouns

- Beyond victimhood, towards citizenship: (Re)conceptualising campus climate for LGBTQ+ university students

See also the chapter on reducing bias in and out of the classroom.

Female Students

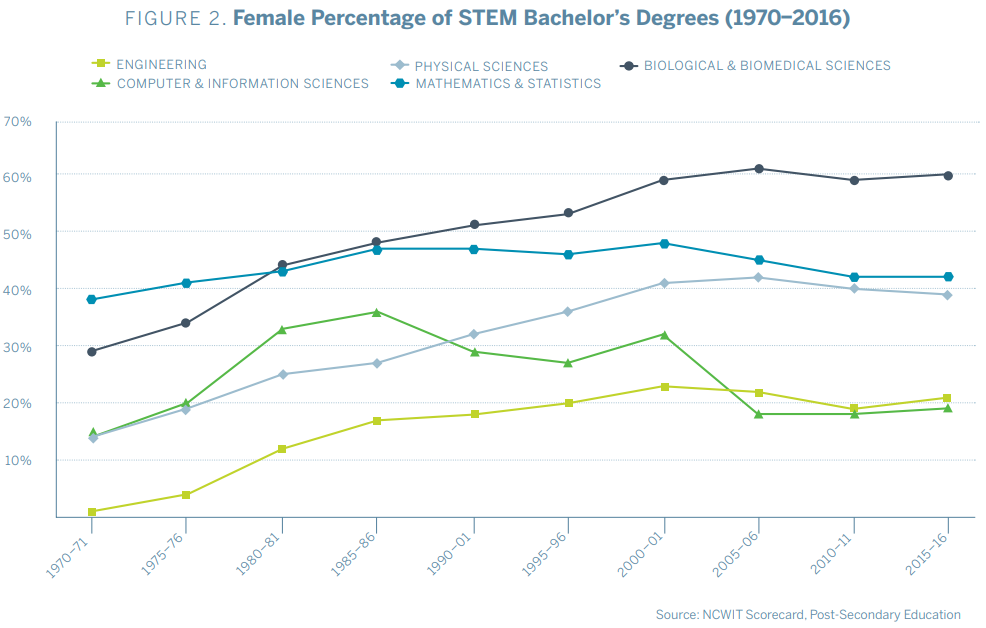

Women have historically been underrepresented in some professional fields of study, in particular STEM fields such as physics, engineering, and computer science. Below is a graph of the percentage female students earning undergraduate STEM degrees by major (via the NCWIT Scorecard on The Status of Women in Computing). Nationwide, only about 20% of engineering and computer science graduates are female (bottom two lines).

Implicit and explicit negative stereotypes about women and other underrepresented groups in STEM affect their interactions and success in school and the workplace.

There is no evidence of innate gender differences in math and science ability, but boys are more likely than girls to pursue careers in math-intensive fields such as engineering and physics. Female STEM majors in college are more likely to drop out, transfer, or change to non-STEM majors than male students. This also is not due to differences in ability. Women are 1.5 times more likely to leave the STEM pipeline after taking Calculus I, for example, partly because of non-academic reasons such as a lack of mathematical confidence.

What are other reasons for why female students may leave STEM majors? One reason involves their “sense of belonging” and their identification and connection with their chosen STEM profession.

“We found that women students who have had either one-on-one contact with, or media exposure to, same-gender professors, experts or peers, feel “I belong here.” This in turn makes them more confident about their abilities, more likely to persist in math, science, and engineering majors, and more interested in pursuing careers in these fields after graduation. This happens when female students see same-gender experts and peers in fields where they are typically a tiny minority, such as engineering, mathematics, computer science, physics, and astronomy” (Dasgupta, 2016).

Strategies for Supporting the Success of Female Students in STEM

What are some strategies you as a faculty member can use in your classroom, your department, and in your interactions with students to help support the success of female students?

- Incorporate stories of the work of women scientists or engineers related to the content of the class, or invite female scientists or engineers to be guest speakers in your class. (Dasgupta, 2016)

- “One of the things that we know works is to use team-based activities to create an environment where you’re not competing for grades and where everyone helps each other. You need an environment which not only values the people who answer the questions first, but tries to engage the entire class — rather than always having one or two people, usually males, dominating the conversation.” (Klawe, 2014)

- When forming teams, instead of trying to equally distribute different types of members, which leads to many teams with only one female student, encourage the formation of teams in which women are not the minority. (Dasgupta, 2016)

- Use a peer mentor system where upper level female students serve as peer mentors to incoming women. Or perhaps invite former students to come speak to your class or meet with your students. “These peer mentors fill a niche that’s different from high-level successful role models because they are closer in age and life stage to their mentees. Peer mentors are a stepping stone on the way to professional success in STEM.” (Dasgupta, 2016)

- Have you and/or your students take one or more of the Harvard implicit bias tests to become more aware of our sometimes unconscious biases again different groups of people.

- Some other strategies shown to be effective (pdf) are listed on the 2nd page of that handout.

- See also “Dear future woman of STEM”: letters of advice from women in STEM

More Resources

- More on Evidence-Based Strategies for Supporting the Success of Female Students

- ‘Belonging’ can help keep talented female students in STEM classes (see the 5 recommendations about what universities can do)

- Can Teaching Spatial Skills Help Bridge the STEM Gender Gap? [yes] (see these resources on spatial visualization skills training)

- Can Test Anxiety Interventions Alleviate a Gender Gap in an Undergraduate STEM Course? [yes] (See this sample stress reappraisal quiz)

- Pedagogical Methods for Improving Women’s Participation and Success in Engineering Education

- Background Info & Data

- Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (AAUW)

- No evidence of innate gender differences in math and science

- Women 1.5 Times More Likely to Leave STEM Pipeline after Calculus Compared to Men: Lack of Mathematical Confidence a Potential Culprit

- Gender in Physics (special issue)

- Why Do So Many Women Who Study Engineering Leave the Field?

- Why So Few Women Are Studying Computer Science

- Female STEM students cite isolation, lack of role models

- Organizations

- National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT)

- Women in Engineering Pro-Active Network (WEPAN) – See the resources on their ENGAGE Engineering site

- Society of Women Engineers (SWE)

Male Students

Male students are less likely to attend college, and they have a lower graduation rate than female students. They are more likely to drop out. Below are some resources describing this issue along with some ideas for addressing it.

- The male college crisis is not just in enrollment, but completion

- Why are so many young men giving up on college?

- A Wake-Up Call to the Student Affairs Profession About Male Students

- Building Belonging to Benefit Black Male Students

- Candid conversations about Black male student success

- Men of Color: First-Year Students Attending a Predominantly White Two-Year Institution

- Latino men and men of color programs: Research-based recommendations for community college practitioners

- A Socio-Ecological Outcome Investigation of the Student Engagement, Achievement, and Satisfaction of Latino Men in Community College Developmental Mathematics

International, Immigrant, and Refugee Students

International students matriculate from other countries and may have to deal with visa issues, cultural and language barriers, as well as more expenses involved with being from out of state. Immigrant and refugee students may not have access to the financial and other supports available to other students.

Teaching and Integrating International Students surveyed the perceptions of international students regarding teaching and learning:

What would international students in American classrooms most want their professors to do differently?

A survey of 662 international students at 23 colleges and universities commissioned by ELS Educational Services found that many international students want their professors to:

-

- Provide more feedback (35 percent identified this as a desired improvement from among a given list of choices).

- Seek to understand international students’ perspectives (33 percent).

- Make classroom materials available after class (32 percent).

- Provide examples of completed assignments (32 percent).

- Provide non-U.S. examples in course contents (28 percent).

More than a third of students — 35 percent — said they felt uncomfortable questioning the opinions of their professors, 30 percent said they felt uncomfortable questioning the opinion of their peers, and 29 percent said they felt uncomfortable speaking in class discussions (the latter proportion was higher among Chinese students, 38 percent of whom said they felt uncomfortable). Nearly a quarter of respondents — 24 percent — said they felt uncomfortable interacting with American students.

More Resources

- History in the Making – stories from immigrant and refugee students at a community college

- Teaching International Students: Six Ways to Smooth the Transition

- Teaching International Students: Pedagogical Issues and Strategies

- The International-Friendly Campus and the International Friendly Campus Scale

- Journal of International Students

- Helping Faculty Teach International Students

- Teaching International Students: Strategies to enhance learning

- Recognizing and Addressing Cultural Variations in the Classroom

- Documenting Their Decisions: How Undocumented Students Enroll and Persist in College

- Special Issue:Equitable and Humanizing Research, Policy, and Practice With and for Undocumented Collegians in the United States

Further Readings

Feedback/Errata