Mitigating Student Resistance

There have long been calls for using evidence-based teaching techniques and technologies in the classroom to improve student success. For example the 2012 “Engage to Excel” report by the Presidential Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) notes that “Classroom approaches that engage students in ‘active learning’ improve retention of information and critical thinking skills.”

Sometimes it may seem risky to try something new or nontraditional in your class, however, partly because of the uncertainty about how students may react. And even when you are not trying anything new at all, some students may passively or even actively show signs of resistance or dissatisfaction, for various reasons.

There are actually many potential barriers to the adoption of evidence-based teaching techniques and technologies, such as: lack of time, insufficient resources or support, and, the topic of this post, the possibility of student resistance, which in turn might negatively impact student satisfaction and ratings.

How can we design and facilitate our courses in order to anticipate and reduce the potential for student resistance? There are several techniques one may employ, many of which are backed by research. First, however, let’s look at the causes and types of student resistance, and then we’ll look at strategies for addressing it.

What is Student Resistance?

The editors of a recent book, Why Students Resist Learning, define student resistance like so:

Student resistance is an outcome, a motivational state in which students reject learning opportunities due to systemic factors.

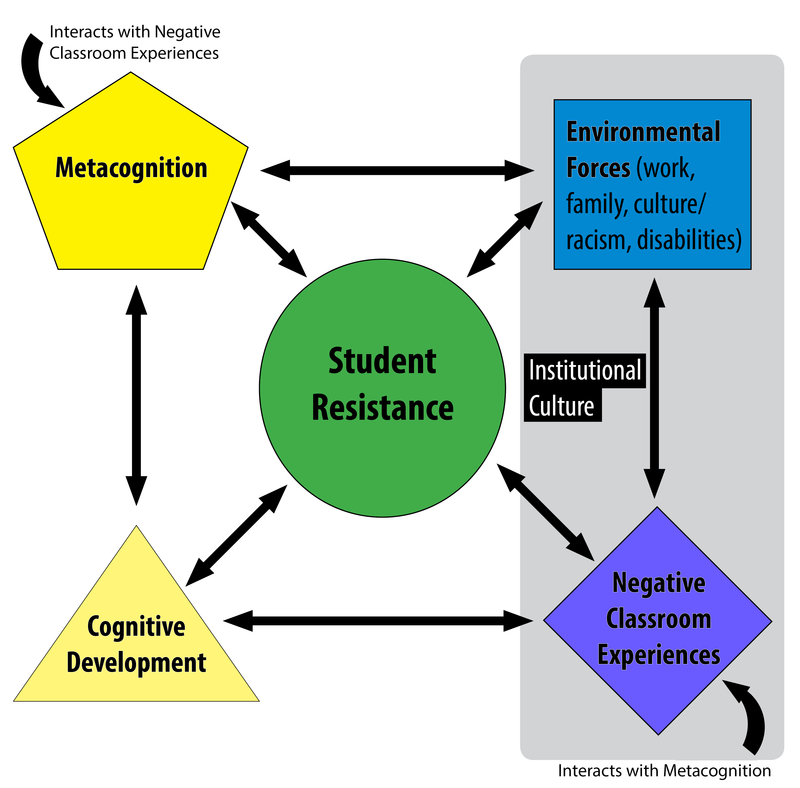

The kinds of systemic factors that may influence resistance are presented in the book’s diagram model of student resistance:

(This image and the one below are via an interview with the book’s editors)

Examples of Student Resistance

Several examples of student resistance are listed in the book. They divide the examples by the type of the resistance (passive or active) and the motivation for the resistance (asserting autonomy or self-preservation):

| Asserting Autonomy

Pushing against external influence Emotions: anger, frustration, resentment |

Self-Preservation

Trying to accommodate external influence Emotions: anxiety, fear |

|

|---|---|---|

| Active Resistance |

|

|

| Passive Resistance |

|

|

Resistance to Group Work

Group work, group projects, group presentations have long been a special source of complaints by students. Here are some common ones from the article “Group Work Can Be Gratifying: Understanding & Overcoming Resistance to Cooperative Learning“:

- “I’ve had bad experiences with group work. Why don’t you just lecture?”

- “I don’t want to rely on strangers. Why can’t I form a group with my friends?”

- “We waste a lot of time in meetings. No one wants to take responsibility.”

- “I don’t know what we are supposed to do or why we are doing it.”

- “I have to do all the work and don’t get the credit. I feel exploited.”

- “The group work just feels like busy work to me. What’s the point?”

- “I worked harder than other people in my group but I got the same grade. That’s unfair.”

If you are using student groups in your courses, consider some of these resources for improving their effectiveness:

- Turning Student Groups into Effective Teams – see especially the forms and notes at the end of the article

- Consider employing Team-based Learning – a well established evidence-based teaching technique. They recently also put out a white paper on best practices for online team-based learning.

Measuring Student Resistance

There has recently been some new research on measuring student resistance that began with the creation of the Student Response to Instructional Practices Survey (StRIP), which includes items related to student resistance:

- I did not actually participate in the activity.

- I gave the activity minimal effort.

- I distracted my peers during the activity.

- I pretended to participate in the activity.

- I surfed the internet, social media, or did something else instead of doing the activity.

- I rushed through the activity.

Other Examples of Student Resistance?

Are there other examples not listed above? Is plagiarism a form of student resistance? Copying homework problems?

How Prevalent is Student Resistance?

The good news is that student resistance is not as widespread as you may think. Several studies and surveys have shown that on average, most students like and prefer when instructors adopt active learning and other innovative teaching strategies and tools (see, e.g., the article “Students’ Expectations, Types of Instruction, and Instructor Strategies Predicting Student Response to Active Learning“).

So it is not as bad a problem as we might think. However, there is still a likelihood of student resistance, especially when you first adopt a new technique. This may be why, for example, some instructors may abandon a new technique after the first semester of trying it.

Strategies for Addressing Student Resistance

Richard Felder and Rebecca Brent, authors of the book Teaching and Learning STEM: A Practical Guide, identify Eight Ways to Defuse Student Resistance, including:

- Ease into new teaching techniques or technologies. For example, if you are trying out flipping the classroom, try it out one week at first before switching the whole course to the technique.

- Explain what you are doing, why you are doing it, and what the benefits are to the students. I’ll share some example explanations below.

- Survey your students about their experiences to get their feedback. I’ll share some example techniques for collecting student feedback below, as well.

In recent research on strategies to mitigate student resistance to active learning (Tharayil et al., 2018), both explanation strategies and facilitation strategies have been identified:

Explanation Strategies

- Providing students with a rationale for using active learning in the classroom by explaining how the activities relate to their learning, connecting the activities with course topics, discussing their relevance to industry

- Communicating overall course expectations for student participation at the beginning of the semester

- Providing explicit instructions about what students are expected to do for a specific active learning exercise

Facilitation Strategies

- Establishing verbal or non-verbal cues such as setting a tone for risk taking, caring about students’ success, encouraging responses by using uncomfortable silences, etc.

- Confronting students who are not participating in activities by physically approaching them, calling on them during more structured lecture, etc.

- Using points or grades to encourage participation

- Walking around the room during active learning instruction

- Encouraging students to provide feedback about an in-class activity

- Prompting students to ask questions about an activity during that activity

- Establishing an “active learning” routine by having a standard type of “bell work,”

- Creating student groups, reframing tasks, etc

- Use incremental activities: giving hints, decomposing a problem into parts,…

Some more concrete details about strategies are listed below.

1. Framing: Explaining to Your Students

Here are some examples of instructors explaining to their students the rationale for using some new teaching technique or technology:

See the Physport series on productively engaging students in active learning for more resources and examples related to framing.

2. Student Testimonials

Instead of you trying to explain the rationale, have former students explain what it takes to succeed in your course.

This is a technique that may not only help reduce potential student anxiety and resistance, but it also has been shown in studies to improve students’ sense of belonging, which in turn reduces equity gaps, including for international students and minority students.

2a. Video Testimonials

You can create or have your students create video testimonials. Here is a “realistic job preview” video by and for students taking courses online:

Here also is a video of students in first year engineering at Ohio State.

2b. Text and Letter Testimonials

You can have your students write letters of advice to next year’s students at the end of a semester.

In a research article on “Closing global achievement gaps in MOOCs,” students read testimonials, such as this one:

“When I first started the course, I worried that I was different from the other students. Everyone else seemed so certain it was the right level for them and were so happy to take it. But I wasn’t sure I fit in – if I would make friends, if people would respect me. Several days after I started, I came to realize that almost everyone who takes the course feels uncertain at first about whether they fit in. It’s something everyone goes through. Now it seems ironic – everybody feels different at first, when really we’re all going through the same things.”

2c. Ask Students to Reflect on the Explanation/Testimonials – Not Just Watch or Read

If you just have students passively watch or read an explanation or testimonial, it may have no impact on improving their success in the course. Here is a sample writing activity students did after reading the aforementioned student testimonial:

Now consider the strategies and insights for how to learn best that you just read. What are your own strategies and insights about how to learn best? And, how are they similar or different to the ones that you just heard about from other students? Please write at least a paragraph. Focus on your thoughts and feelings, and don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or how well written it is.

2d. Generating / Creating Student Testimonials

You’ll also have to think about how you will collect and present student testimonials. Will you ask former students to visit your class and speak with the current students? Or create a video or collect written testimonials? Here is how student testimonials were collected in the aforementioned article:

New students really appreciate hearing directly from students who already have some experience with learning in an online course. To give the new incoming learners a chance to hear directly from somewhat more experienced learners, we would like you to write a note to an incoming learner about your experience and what you’ve learned so far. Write about how they may feel unsure at first of their belonging in the online course but ultimately come to feel that they belong. We will give your note to a student who enrolls in the course for similar reasons as yourself, so you can imagine it is a student like you. We know it can be difficult to write that way, but we believe it will be particularly meaningful for new learners if they feel as though a more experienced learner is speaking directly to them.

The remaining strategies for addressing student resistance are related to soliciting feedback from your students about your teaching and the course. By getting their feedback early and throughout the semester, you can make adjustments that will help improve student satisfaction and learning and reduce student resistance, as opposed to waiting for the traditional end of course survey when it is too late to make changes for those students.

3. Midterm Student Feedback

Midterm Student Feedback (MSF) involves collecting feedback from students near the start or middle of a course in order to give the instructor an opportunity to make adjustments and improvements. Usually an outside consultant collects the feedback and provides guidance for the instructor on translating the feedback into positive changes in the course. The entire process is confidential to the instructor and anonymous for the students.

You can also survey students yourself. See this Stop-Go-Change activity.

Here are some different examples of questions that you might ask of your students:

- via Clark & Redmond (1982)

- What do you like about the course?

- What do you think needs improvement?

- What suggestions do you have for bringing about those improvements?

- via Simmons College and others

- What do you like most about this course and/or the instructor’s teaching of it?

- What about this course and/or the instructor’s teaching of it needs change or improvement?

- What suggestions can you offer that would help make this course a better learning experience for you?

- via U. Michigan

- What are the major strengths in this course?

- What changes could be made in the course to assist you in learning?

See the MSF Guidebook for more examples and details.

4. Minute Papers, Exit Tickets

You can also collect feedback from students yourself by asking students to answer questions at the end of class (exit ticket) or the end of an assignment or module. Here are some examples of the types of questions you might be interested in asking.

- What was the most important point of the class?

- What question remains unanswered in your mind?

- What question from this class might appear on the next quiz/test?

- What was the muddiest point of the class?

- What was the main concept illustrated by the in-class demonstration/experiment?

Here are some of the types of questions you might want to ask when your students turn in a paper assignment:

- Paper 1: I’m most satisfied with . . . I’m least satisfied with . . . I’m having problems with . . .

- Paper 2: In writing this essay, what did you learn that surprised you? When editing your paper, what were you unsure about?

- Paper 3: Point out specific places in your argument at which you were aware of accommodating your audience (their knowledge or attitudes). Point out places in which you used sentences for rhetorical effect.

- Paper 4: Why did you choose this particular arrangement?

What would you do differently if you had more time?

See bit.ly/minutepapers for a longer list of potential questions.

How will you collect feedback from students to improve upon what you are doing in your courses? Doing so may also help reduce student resistance, as well.

More Resources

You can find some handouts and slides related to the topic of addressing student resistance here: bit.ly/studentresist

Feedback/Errata