8

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key elements of psychosocial theory of identity development

- Explain strategies utilized to implement psychosocial theory of identity development

- Summarize the criticisms of and educational implications of psychosocial theory of identity development

- Explain how equity is impacted by psychosocial theory of identity development

- Identify classroom strategies to support the use of psychosocial theory of identity development.

- Select strategies to support student success utilizing psychosocial theory of identity development.

- Develop a plan to implement the use of psychosocial theory of identity development.

Image 8.1

SCENARIO:

Mr. Bates was planning his lesson on the Oregon Trail for his fourth graders. Last year, he used an online curriculum and it all felt a little stale when he tried to deliver it. Kids were kind of bored, which frustrated Mr. Bates because he had followed the trail the prior summer and had interacted with a lot of live history. Mr. Bates loved history, especially local history! This year, he wanted to do something different, something that would allow students maximum choice in their projects in terms of content and presentation. He also wanted to expose students to the topic in a variety of ways: field trips, film, and the online Oregon Trail game to appeal to all of his diverse learners. Mr. Bates recognized that his kids did not all learn the same way and this had to do with their psychosocial development.

As you read about Erikson’s psychosocial theory of identity development, consider how options for learning and student choice create opportunities for strong engagement. Creating more options and building student autonomy ensures that educators are meeting students where they are!

Check out the following videos as an introduction:

Video 8.1: “Erikson’s Psychosocial Development”

Video 8.2: “Erik Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development Explained”

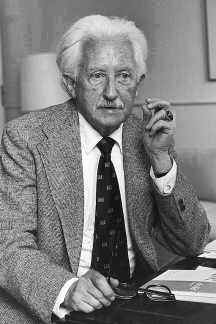

Image 8.2: Erik Erikson

INTRODUCTION

Erik H. Erikson (1902-1994), was born in Germany. He was a world-renowned scholar of the behavioral sciences, and his contributions ranged from psychology to anthropology. Moreover, his two biographies, one of Gandhi, the other a Pulitzer-Prize study of Martin Luther, earned him distinction in literature. Serious students of personality theory underscored his seminal contribution: linking individual development to external forces (structured as the “Life Cycle,” the stages ranging from infancy to adulthood). Rather than the negations of pathology, Erikson welcomed the affirmation of human strength, stressing always the potential of constructive societal input in personality development. Erikson’s dual concepts of an (individual) ego and group identity have become an integral part of group psychology, with terms such as adolescent “identity diffusion” or adolescent “moratorium” having been mainstreamed into everyday language.

In 1933, when the Nazi power was gaining power in Germany, Erikson, his wife, and young son left for the US. The Eriksons settled first in Boston and Erikson began teaching at Harvard Medical School, in addition to his work under Henry A. Murray at the university’s Psychology Clinic. It was here he met Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, Ruth Benedict, and Kurt Lewin. In 1936, Erikson moved to Yale University where he was attached to both the medical school and to the Yale Institute of Human Relations. His first field study of the Sioux Indians in South Dakota was launched from New Haven. The subsequent work with the Yurok Indians, commenced after he had gone to the University of California in 1939 to join Jean MacFarlane’s longitudinal study of personality development. During World War II, Erikson did research for the U.S. Government, including an original study of “Submarine Psychology.” In 1950, the same year in which his book Childhood and Society was published, Erikson resigned from the University of California. Though not a Communist, he refused to sign the loyalty contract stating, that “…my conscience did not permit me,” to collaborate with witch hunters. He returned to Harvard in the 1960s as a professor of human development and remained there until his retirement in 1970. In 1973 the National Endowment for the Humanities selected Erikson for the Jefferson Lecture, the United States’ highest honor for achievement in the humanities.

Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, as articulated by Erik Erikson, in collaboration with his wife Joan Erikson (Thomas, 1997), is a comprehensive psychoanalytic theory that identifies a series of eight stages, in which a healthy developing individual should pass through from infancy to late adulthood.

All stages are present at birth but only begin to unfold according to both a natural scheme and one’s ecological and cultural upbringing. In each stage, the person confronts, and hopefully masters, new challenges. Each stage builds upon the successful completion of earlier stages. The challenges of stages not successfully completed may be expected to reappear as problems in the future.

However, mastery of a stage is not required to advance to the next stage. The outcome of one stage is not permanent and can be modified by later experiences. Erikson’s stage theory characterizes an individual advancing through the eight life stages as a function of negotiating his or her biological forces and sociocultural forces. Each stage is characterized by a psychosocial crisis of these two conflicting forces (Figure 8.1). If an individual does indeed successfully reconcile these forces (favoring the first mentioned attribute in the crisis), he or she emerges from the stage with the corresponding virtue (Figure 8.1). For example, if an infant enters into the toddler stage (autonomy vs. shame and doubt) with more trust than mistrust, he or she carries the virtue of hope into the remaining life stages (Crain, 2011).

Figure 8.1: Psychosocial Identity Development Stages, Virtues, and Crisis

|

Stage: Approximate Age |

Virtues |

Psychosocial Crisis |

Significant Relationship |

Existential Question |

Examples |

|

Infancy 0-2 Years |

Hope |

Trust vs. Mistrust |

Mother |

Can I trust the world? |

Feeding; Abandonment |

|

Early Childhood 2-4 Years |

Will |

Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt |

Parents |

Is it okay to be me? |

Toilet Training; Clothing Themselves |

|

Preschool Age 4-5 Years |

Purpose |

Initiative vs. Guilt |

Family |

Is it okay for me to do, move, and act? |

Exploring; Using Tools or Making Art |

|

School Age 5-12 Years |

Competence |

Industry vs. Inferiority |

Neighbors School |

Can I make it in the world of people and things? |

School; Sports |

|

Adolescence 13-19 Years |

Fidelity |

Identity vs. Role Confusion |

Peers Role Model |

Who am I? Who can I be? |

Social Relationships |

|

Early Adulthood 20-39 Years |

Love |

Intimacy vs. Isolation |

Friends Partners |

Can I love? |

Romantic Relationships |

|

Adulthood 40-64 Years |

Care |

Generativity vs. Stagnation |

Household Workmates |

Can I make my life count? |

Work; Parenthood |

|

Maturity 65-Death |

Wisdom |

Ego Integrity vs. Despair |

Mankind My kind |

Is it okay to have been me? |

Reflection on Life |

Stages of Psychosocial Identity Development

Hope: Trust vs. Mistrust (Infancy, 0-2 years)

Existential Question: Can I Trust the World?

The first stage of Erik Erikson’s theory centers around the infant’s basic needs being met by the parents/guardians and this interaction leading to trust or mistrust. Trust as defined by Erikson is an essential trustfulness of others as well as a fundamental sense of one’s own trustworthiness (Sharkey, 1997). The infant depends on the parents, especially the mother, for sustenance and comfort. The child’s relative understanding of the world and society comes from the parents and their interaction with the child.

A child’s first trust is always with the parent or caregiver; whomever that might be; however, even the caregiver is secondary whereas the parents are primary in the eyes of the child. If the parents expose the child to warmth, regularity, and dependable affection, the infant’s view of the world will be one of trust. Should the parents fail to provide a secure environment and to meet the child’s basic needs; a sense of mistrust will result (Bee & Boyd, 2009). Development of mistrust can lead to feelings of frustration, suspicion, withdrawal, and a lack of confidence (Sharkey, 1997).

According to Erik Erikson, the major developmental task in infancy is to learn whether or not other people, especially primary caregivers, regularly satisfy basic needs. If caregivers are consistent sources of food, comfort, and affection, an infant learns trust-that others are dependable and reliable. If they are neglectful, or perhaps even abusive, the infant instead learns mistrust-that the world is an undependable, unpredictable, and possibly a dangerous place. While negative, having some experience with mistrust allows the infant to gain an understanding of what constitutes dangerous situations later in life; yet being at the stage of infant or toddler, it is a good idea not to put them in situations of mistrust: the child’s number one needs are to feel safe, comforted, and well cared for (Bee & Boyd, 2009).

Will: Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (Early Childhood, 2-4 years)

Existential Question: Is It Okay to Be Me?

As the child gains control over eliminative functions and motor abilities, they begin to explore their surroundings. The parents still provide a strong base of security from which the child can venture out to assert their will. The parents’ patience and encouragement helps foster autonomy in the child. Children at this age like to explore the world around them and they are constantly learning about their environment. Caution must be taken at this age while children may explore things that are dangerous to their health and safety.

At this age children develop their first interests. For example, a child who enjoys music may like to play with the radio. Children who enjoy the outdoors may be interested in animals and plants. Highly restrictive parents, however, are more likely to instill in the child a sense of doubt, and reluctance to attempt new challenges. As they gain increased muscular coordination and mobility, toddlers become capable of satisfying some of their own needs. They begin to feed themselves, wash and dress themselves, and use the bathroom.

If caregivers encourage self-sufficient behavior, toddlers develop a sense of autonomy-a sense of being able to handle many problems on their own. But if caregivers demand too much too soon, refuse to let children perform tasks of which they are capable, or ridicule early attempts at self-sufficiency, children may instead develop shame and doubt about their ability to handle problems.

Purpose: Initiative vs. Guilt (Preschool, 4-5 years)

Existential Question: Is it Okay for Me to Do, Move, and Act?

Initiative adds to autonomy the quality of undertaking, planning and attacking a task for the sake of just being active and on the move. The child is learning to master the world around them, learning basic skills and principles of physics. Things fall down, not up. Round things roll. They learn how to zip and tie, count and speak with ease. At this stage, the child wants to begin and complete their own actions for a purpose. Guilt is a confusing new emotion. They may feel guilty over things that logically should not cause guilt. They may feel guilt when this initiative does not produce desired results.

The development of courage and independence are what set preschoolers, ages three to six years of age, apart from other age groups. Young children in this category face the challenge of initiative versus guilt. As described in Bee and Boyd (2009), the child during this stage faces the complexities of planning and developing a sense of judgment. During this stage, the child learns to take initiative and prepare for leadership and goal achievement roles. Activities sought out by a child in this stage may include risk-taking behaviors, such as crossing a street alone or riding a bike without a helmet; both these examples involve self-limits.

Within instances requiring initiative, the child may also develop negative behaviors. These behaviors are a result of the child developing a sense of frustration for not being able to achieve a goal as planned and may engage in behaviors that seem aggressive, ruthless, and overly assertive to parents. Aggressive behaviors, such as throwing objects, hitting, or yelling, are examples of observable behaviors during this stage.

Preschoolers are increasingly able to accomplish tasks on their own, and can start new things. With this growing independence comes many choices about activities to be pursued. Sometimes children take on projects they can readily accomplish, but at other times they undertake projects that are beyond their capabilities or that interfere with other people’s plans and activities. If parents and preschool teachers encourage and support children’s efforts, while also helping them make realistic and appropriate choices, children develop initiative-independence in planning and undertaking activities. But if, instead, adults discourage the pursuit of independent activities or dismiss them as silly and bothersome, children develop guilt about their needs and desires (Rao, 2012).

Competence: Industry vs. Inferiority (School Age, 5-12 Years)

Existential Question: Can I Make it in the World of People and Things?

The aim to bring a productive situation to completion gradually supersedes the whims and wishes of play. The fundamentals of technology are developed. The failure to master trust, autonomy, and industrious skills may cause the child to doubt his or her future, leading to shame, guilt, and the experience of defeat and inferiority (Erik Erikson’s Stages of Social-Emotional Development, n.d.). The child must deal with demands to learn new skills or risk a sense of inferiority, failure, and incompetence.

Children at this age are becoming more aware of themselves as “individuals.” They work hard at “being responsible, being good and doing it right.” They are now more reasonable to share and cooperate. Allen and Marotz (2003) also list some perceptual cognitive developmental traits specific for this age group. Children grasp the concepts of space and time in more logical, practical ways. They gain a better understanding of cause and effect, and of calendar time. At this stage, children are eager to learn and accomplish more complex skills: reading, writing, telling time. They also get to form moral values, recognize cultural and individual differences and are able to manage most of their personal needs and grooming with minimal assistance (Allen & Marotz, 2003). At this stage, children might express their independence by talking back and being disobedient and rebellious.

Erikson viewed the elementary school years as critical for the development of self-confidence. Ideally, elementary school provides many opportunities to achieve the recognition of teachers, parents and peers by producing things-drawing pictures, solving addition problems, writing sentences, and so on. If children are encouraged to make and do things and are then praised for their accomplishments, they begin to demonstrate industry by being diligent, persevering at tasks until completed, and putting work before pleasure. If children are instead ridiculed or punished for their efforts or if they find they are incapable of meeting their teachers’ and parents’ expectations, they develop feelings of inferiority about their capabilities (Crain, 2011).

At this age, children start recognizing their special talents and continue to discover interests as their education improves. They may begin to choose to do more activities to pursue that interest, such as joining a sport if they know they have athletic ability, or joining the band if they are good at music. If not allowed to discover their own talents in their own time, they will develop a sense of lack of motivation, low self-esteem, and lethargy.

Fidelity: Identity vs. Role Confusion (Adolescence, 13-19 Years)

Existential Question: Who Am I and What Can I Be?

The adolescent is newly concerned with how they appear to others. Superego identity is the accrued confidence that the outer sameness and continuity prepared in the future are matched by the sameness and continuity of one’s meaning for oneself, as evidenced in the promise of a career. The ability to settle on a school or occupational identity is pleasant. In later stages of adolescence, the child develops a sense of sexual identity. As they make the transition from childhood to adulthood, adolescents ponder the roles they will play in the adult world. Initially, they are apt to experience some role confusion-mixed ideas and feelings about the specific ways in which they will fit into society-and may experiment with a variety of behaviors and activities (e.g. tinkering with cars, baby-sitting for neighbors, affiliating with certain political or religious groups). Eventually, Erikson proposed, most adolescents achieve a sense of identity regarding who they are and where their lives are headed. The teenager must achieve identity in occupation, gender roles, politics, and, in some cultures, religion.

Erikson is credited with coining the term “identity crisis” (Gross, 1987, p. 47). Each stage that came before and that follows has its own “crisis” but even more so now, for this marks the transition from childhood to adulthood. This passage is necessary because “Throughout infancy and childhood, a person forms many identifications. But the need for identity in youth is not met by these” (Wright, 1982, p. 73). This turning point in human development seems to be the reconciliation between “the person one has come to be” and “the person society expects one to become.” This emerging sense of self will be established by “forging” past experiences with anticipations of the future. In relation to the eight life stages as a whole, the fifth stage corresponds to the crossroads.

What is unique about the stage of Identity is that it is a special sort of synthesis of earlier stages and a special sort of anticipation of later ones. Youth has a certain unique quality in a person’s life; it is a bridge between childhood and adulthood. Youth is a time of radical change-the great body changes accompanying puberty, the ability of the mind to search one’s own intentions and the intentions of others, the suddenly sharpened awareness of the roles society has offered for later life (Gross, 1987).

Adolescents “are confronted by the need to re-establish [boundaries] for themselves and to do this in the face of an often potentially hostile world” (Stevens, 1983, pp. 48-50). This is often challenging since commitments are being asked for before particular identity roles have formed. At this point, one is in a state of “identity confusion” but society normally makes allowances for youth to “find themselves” and this state is called “the moratorium.”

The challenge of adolescence is one of role confusion-a reluctance to commit which may haunt a person into his mature years. Given the right conditions-and Erikson believes these are essentially having enough space and time, a psychosocial moratorium, when a person can freely experiment and explore-what may emerge is a firm sense of identity, an emotional and deep awareness of who they are (Stevens, 1983, pp. 48-50).

No matter how one has been raised, one’s personal ideologies are now chosen for oneself. Often, this leads to conflict with adults over religious and political orientations. Another area where teenagers are deciding for themselves is their career choice, and sometimes parents want to have some input. If society is too insistent, the teenager will acquiesce to external wishes, effectively forcing them to ‘foreclose’ on experimentation and, therefore, true self-discovery. Once someone settles on a worldview and vocation, will they be able to integrate this aspect of self-definition into a diverse society? According to Erikson, when an adolescent has balanced both perspectives of “What have I got?” and “What am I going to do with it?” he or she has established their identity (Gross, 1987). Dependent on this stage is the ego quality of fidelity-the ability to sustain loyalties freely pledged in spite of the inevitable contradictions and confusions of value systems (Stevens, 1983).

Given that the next stage (Intimacy) is often characterized by marriage, many are tempted to cap off the fifth stage at 20 years of age. However, these age ranges are actually quite fluid, especially for the achievement of identity, since it may take many years to become grounded, to identify the object of one’s fidelity, to feel that one has “come of age”. In the biographies Young Man Luther and Gandhi’s Truth, Erikson determined that their crises ended at ages 25 and 30, respectively.

Erikson does note that the time of Identity crisis for persons of genius is frequently prolonged. He further notes that in our industrial society, identity formation tends to be long, because it takes us so long to gain the skills needed for adulthood’s tasks in our technological world. That means that we do not have an exact time span in which to find ourselves. It doesn’t happen automatically at eighteen or at twenty-one. A very approximate rule of thumb for our society would put the end somewhere in one’s twenties (Gross, 1987).

Love: Intimacy vs. Isolation (Early Adulthood, 20-39 years)

Existential Question: Can I Love?

The Intimacy vs. Isolation conflict is emphasized around the age of 30. At the start of this stage, identity vs. role confusion is coming to an end, though it still lingers at the foundation of the stage (Erikson, 1950). Young adults are still eager to blend their identities with friends. They want to fit in. Erikson believes we are sometimes isolated due to intimacy. We are afraid of rejections such as being turned down or our partners breaking up with us. We are familiar with pain and to some of us rejection is so painful that our egos cannot bear it. Erikson also argues that “Intimacy has a counterpart: Distantiation: the readiness to isolate and if necessary, to destroy those forces and people whose essence seems dangerous to our own, and whose territory seems to encroach on the extent of one’s intimate relations” (Erikson, 1950, p. 237).

Once people have established their identities, they are ready to make long-term commitments to others. They become capable of forming intimate, reciprocal relationships (e.g. through close friendships or marriage) and willingly make the sacrifices and compromises that such relationships require. If people cannot form these intimate relationships-perhaps because of their own needs-a sense of isolation may result; arousing feelings of darkness and angst.

Care: Generativity vs. Stagnation (Adulthood, 40-64 years)

Existential Question: Can I Make My Life Count?

Generativity is the concern of guiding the next generation. Socially-valued work and disciplines are expressions of generativity. The adult stage of generativity has broad application to family, relationships, work, and society. “Generativity, then, is primarily the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation… the concept is meant to include… productivity and creativity” (Erikson, 1950, p. 240).

During middle age, the primary developmental task is one of contributing to society and helping to guide future generations. When a person makes a contribution during this period, perhaps by raising a family or working toward the betterment of society, a sense of generativity-a sense of productivity and accomplishment-results. In contrast, a person who is self-centered and unable or unwilling to help society move forward develops a feeling of stagnation-a dissatisfaction with the relative lack of productivity.

Central tasks of middle adulthood are to:

• Express love through more than sexual contacts

• Maintain healthy life patterns

• Develop a sense of unity with partner

• Help growing and grown children to be responsible adults

• Relinquish central role in lives of grown children

• Accept children’s mates and friends

• Create a comfortable home

• Be proud of accomplishments of self and mate/spouse

• Reverse roles with aging parents

• Achieve mature, civic and social responsibility

• Adjust to physical changes of middle age

• Use leisure time creatively

Wisdom: Ego Integrity vs. Despair (Maturity, 65-Death)

Existential Question: Is it Okay to Have Been Me?

As we grow older and become senior citizens we tend to slow down our productivity and explore life as a retired person. It is during this time that we contemplate our accomplishments and are able to develop integrity if we see ourselves as leading a successful life. If we see our life as unproductive, or feel that we did not accomplish our life goals, we become dissatisfied with life and develop despair, often leading to depression and hopelessness.

The final developmental task is retrospection: people look back on their lives and accomplishments. They develop feelings of contentment and integrity if they believe that they have led a happy, productive life. They may instead develop a sense of despair if they look back on a life of disappointments and unachieved goals. This stage can occur out of the sequence when an individual feels they are near the end of their life (such as when receiving a terminal disease diagnosis).

Ninth Stage

Joan M. Erikson, who married and collaborated with Erik Erikson, added a ninth stage in The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version (Erikson & Erikson, 1998). Living in the ninth stage, she wrote, “old age in one’s eighties and nineties brings with it new demands, reevaluations, and daily difficulties” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, p. 4). Addressing these new challenges requires “designating a new ninth stage.” Erikson was ninety-three years old when she wrote about the ninth stage (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, p. 105).

Joan Erikson showed that all the eight stages “are relevant and recurring in the ninth stage” (Mooney, 2007, p. 78). In the ninth stage, the psychosocial crises of the eight stages are faced again, but with the quotient order reversed. For example, in the first stage (infancy), the psychosocial crisis was “Trust vs. Mistrust” with Trust being the “syntonic quotient” and Mistrust being the “diatonic” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, p. 106). Joan Erikson applies the earlier psychosocial crises to the ninth stage as follows:

- Basic Mistrust vs. Trust: Hope

In the ninth stage, “elders are forced to mistrust their own capabilities” because one’s “body inevitably weakens.” Yet, Joan Erikson asserts that “while there is light, there is “hope” for a “bright light and revelation” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 106-107).

- Shame and Doubt vs. Autonomy: Will

Ninth stage elders face the “shame of lost control” and doubt “their autonomy over their own bodies.” So it is that “shame and doubt challenge cherished autonomy” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 107-108).

- Inferiority vs. Industry: Competence

Industry as a “driving force” that elders once had is gone in the ninth stage. Being incompetent “because of aging is belittling” and makes elders “like unhappy small children of great age” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, p. 109).

- Identity Confusion vs. Identity: Fidelity

Elders experience confusion about their “existential identity” in the ninth stage and “a real uncertainty about status and role” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 109-110).

- Isolation vs. Intimacy: Love

In the ninth stage, the “years of intimacy and love” are often replaced by “isolation and deprivation.” Relationships become “overshadowed by new incapacities and dependencies” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 110-111).

- Stagnation vs. Generativity: Care

The generativity in the seventh stage of “work and family relationships” if it goes satisfactorily, is “a wonderful time to be alive.” In one’s eighties and nineties, there is less energy for generativity or caretaking. Thus, “a sense of stagnation may well take over” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 111-112).

- Despair and Disgust vs. Integrity: Wisdom

Integrity imposes “a serious demand on the senses of elders.” Wisdom requires capacities that ninth stage elders “do not usually have.” The eighth stage includes retrospection that can evoke a “degree of disgust and despair.” In the ninth stage, introspection is replaced by the attention demanded to one’s “loss of capacities and disintegration” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 112-113).

Living in the ninth stage, Joan Erikson expressed confidence that the psychosocial crisis of the ninth stage can be met as in the first stage with the “basic trust” with which “we are blessed” (Erikson & Erikson, 1998, pp. 112-113). Erikson saw a dynamic at work throughout life, one that did not stop at adolescence. He also viewed the life stages as a cycle: the end of one generation was the beginning of the next. Seen in its social context, the life stages were linear for an individual but circular for societal development (Erikson, 1950). Erik Erikson believed that development continues throughout life. Erikson took the foundation laid by Freud and extended it through adulthood and into late life (Kail & Cavanaugh, 2004).

Criticism of the Psychosocial Theory of Identity Development

Erikson’s theory may be questioned as to whether his stages must be regarded as sequential, and only occurring within the age ranges he suggests. There is debate as to whether people only search for identity during the adolescent years or if one stage needs to happen before other stages can be completed. However, Erikson states that each of these processes occur throughout the lifetime in one form or another, and he emphasizes these “phases” only because it is at these times that the conflicts become most prominent (Erikson, 1956).

Most empirical research into Erikson has related to his views on adolescence and attempts to establish identity. His theoretical approach was studied and supported, particularly regarding adolescence, by James E. Marcia. Marcia’s work (1966) has distinguished different forms of identity, and there is some empirical evidence that those people who form the most coherent self-concept in adolescence are those who are most able to make intimate attachments in early adulthood. This supports Eriksonian theory in that it suggests that those best equipped to resolve the crisis of early adulthood are those who have most successfully resolved the crisis of adolescence.

Educational Implications

Teachers who apply psychosocial development in the classroom create an environment where each child feels appreciated and is comfortable with learning new things and building relationships with peers without fear (Hooser, 2010). Teaching Erikson’s theory at the different grade levels is important to ensure that students will attain mastery of each stage in Erikson’s theory without conflict. There are specific classroom activities that teachers can incorporate into their classroom during the three stages that include school age children. The activities listed below are just a few suggested examples that apply psychosocial development.

At the preschool level, teachers want to focus on developing a hardy personality.

Classroom examples that can be incorporated at the Preschool Level:

1. Find out what students are interested in and create projects that incorporate their area of interest.

2. Let the children be in charge of the learning process when participating in a classroom project. This will exhibit teacher appreciation for the areas of interest of the students as well as confidence in their ability.

3. Make sure to point out and praise students for good choices.

4. Offer continuous feedback on work that has been completed.

5. Do not ridicule or criticize students openly. Find a private place to talk with a child about a poor choice or behavior. Help students formulate their own alternate choices by guiding them to a positive solution and outcome.

6. When children experiment, they should not be punished for trying something that may turn out differently than the teacher planned.

7. Utilize physical activity to teach fairness and sportsmanship (Bianca, 2010).

Teachers should focus on achievement and peer relationships at the Elementary Level.

Classroom examples that can be incorporated at the Elementary Level:

1. Create a list of classroom duties that need to be completed on a scheduled basis. Ask students for their input when creating the list as well as who will be in charge of what.

2. Discuss and post classroom rules. Make sure to include students in the decision-making process when discussing rules.

3. Encourage students to think outside of their day-to-day routine by role playing different situations.

4. Let students know that striving for perfection is not as important as learning from mistakes. Teach them to hold their head high and move forward.

5. Encourage children to help students who may be having trouble socially and/or academically. Never allow any child to make fun of or bully another child.

6. Build confidence by recognizing success in what children do best.

7. Provide a variety of choices when making an assignment so that students can express themselves with a focus on their strengths.

8. Utilize physical activity to build social development and to help students appreciate their own abilities as well as the abilities of others (Bianca, 2010).

During the middle and high school years, building identity and self-esteem should be part of a teacher’s focus.

Classroom examples that can be incorporated at the Middle School and High School Level:

1. Treat all students equally. Do not show favoritism to a certain group of students based on gender, race, ability, academic skills, sexual orientation, or socioeconomic status.

2. Incorporate guest speakers and curriculum activities from as many areas as possible so as to expose students to many career choices.

3. Encourage students to focus on their strengths and acknowledge them when they exhibit work that incorporates these strengths.

4. Encourage students to develop confidence by trying different approaches to solving problems.

5. Incorporate life skills into lesson planning to increase confidence and self-sufficiency.

6. Utilize physical activity to help relieve stress, negative feelings and improve moods (Bianca, 2010).

Chapter Discussion Questions:

- Explain the benefits of psychosocial theory of identity development to support student success.

- How would you summarize psychosocial theory of identity development?

- How would you use psychosocial theory of identity development to support your students?

- How is equity related to psychosocial theory of identity development?

ATTRIBUTIONS

Image 8.1: “Friends and Family” by Mike Watson Images Limited is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Image 8.2: “Erik Erikson citáty” by Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Image 8.3: “Eldre, Karen Beate Nosterud” by Karen Beate Nøsterud is licensed under CC BY 2.5

Video 8.1: “Erikson’s Psychosocial Development” by Shreena Desai, Khan Academy

Video 8.2: “Erik Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development Explained” by Learn My Test

REFERENCES

Allen, E., & Marotz, L. (2003). Developmental profiles pre-Birth through twelve (4th ed.). Albany, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning.

Bee, H., & Boyd, D. (2009, March). The developing child (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Bianca, A. (2010, June 4). Psychosocial development in physical activity. Retrieved from

http://www.ehow.com/about_6587070_psychosocial-development-physical-activity.htm

Crain, W. (2011). Theories of development: Concepts and applications (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Erik Erikson’s stages of social-emotional development. (n.d.). Retrieved from

https://childdevelopmentinfo.com/child-development/erickson/#ixzz3ZaBI7RQf

Erik Erikson’s 8 stages of psychosocial development. (n.d.). Retrieved from

http://web.cortland.edu/andersmd/ERIK/stageint.HTML

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1956). The problem of ego identity. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 4, 56-121. doi: 10.1177/000306515600400104.

Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1998). The life cycle completed: Extended version. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Gross, F. L. (1987). Introducing Erik Erikson: An invitation to his thinking. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Hooser, T. C. V. (2010, November 28). How to apply psychosocial development in the classroom. Retrieved from http://www.ehow.com/how_7566430_apply-psychosocial-development-classroom.html

Kail, R. V., & Cavanaugh, J. C. (2004). Human development: A life-span view (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Macnow, A. S. (Ed.). (2014). MCATbehavioral science review. New York, NY: Kaplan Publishing.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551-558.doi:10.1037/h0023281

Mooney, J. (2007). Erik Erikson. In Joe L. Kincheloe & Raymond A. Horn (Eds.), The praeger handbook of education and psychology (Vol. 1, p. 78). Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=O1ugEIEid6YC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Praeger+Handbook+of+Education+a nd+Psychology&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjWnfK7i_DWAhWDwiYKHdrjAooQ6AEIJjAA#v=onepage&q=The%20 Praeger%20Handbook%20of%20Education%20and%20Psychology&f=false

Rao, A. (Ed.). (2012, July). Principles and practice of pedodontics (3rd ed.). Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=Ynaeb6CC8wAC&pg=PA62&lpg=PA62&dq=discourage+the+pursuit+of+independe

nt+activities+or+dismiss+them+as+silly+and+bothersome,+children+develop+guilt+about+their+needs+and+desires&source=bl&ots=R-A9YrkvAH&sig=DNUdrJgZsnT96jXA8FipC64eDQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjnstb0je_WAhWHQyYKHfkpCXUQ6AEINjAD#v=onepage&q=discourage%20the%20pursuit%20of%20independent%20activities%20or%20dismiss%20them%20as%20silly%20and%20bothersome%2C%20children%20develop%20guilt%20about%20their%20needs%20and%20desires&f=false

Sharkey, W. (1997, May). Erik Erikson. Retrieved from

http://www.muskingum.edu/~psych/psycweb/history/erikson.htm

Stevens, R. (1983). Erik Erikson: An introduction. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Thomas, R. M. (1997, August 8). Joan Erikson is dead at 95: Shaped thought on life cycles. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1997/08/08/us/joan-erikson-is-dead-at-95-shaped-thought-on-life-cycles.html.

Wright, J. E. (1982). Erikson: Identity and religion. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

ADDITIONAL READING

Credible Articles on the Internet:

Davis, D., & Clifton, A. (1999). Psychosocial theory: Erikson. Retrieved from

http://www.haverford.edu/psych/ddavis/p109g/erikson.stages.html

Erikson, R. (2010). ULM Classroom Management. Retrieved from

https://ulmclassroommanagement.wikispaces.com/Erik+Erikson

Krebs-Carter, M. (2008). Ages in stages: An exploration of the life cycle based on Erik Erikson’s eight stages of human development. Retrieved from http://www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1980/1/80.01.04.x.html

McLeod. S. (2017). Erik Erikson. Retrieved from

https://www.simplypsychology.org/Erik-Erikson.html

Ramkumar, S. (2002). Erik Erikson’s theory of development: A teacher’s observations. Retrieved from

http://www.journal.kfionline.org/issue-6/erik-eriksons-theory-of-development-a-teachers-observations

Sharkey, W. (1997). Erik Erikson. Retrieved from

http://www.muskingum.edu/~psych/psycweb/history/erikson.htm

Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles:

Capps, D. (2004). The decades of life: Relocating Erikson’s stages. Pastoral Psychology, 53(1), 3-32.

Christiansen, S. L., & Palkovitz, R. (1998). Exploring Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development: Generativity and its relationship to paternal identity, intimacy, and involvement in childcare. Journal of Men’s Studies, 7(1), 133-156.

Coughlan, F., & Welsh-Breetzke, A. (2002). The circle of courage and Erikson’s psychosocial stages.

Reclaiming Children and Youth, 10 (4), 222-226.

Domino, G., & Affonso, D. D. (1990). A personality measure of Erikson’s life stages: The inventory of psychosocial balance. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54, (3&4), 576-588.

Kidwell, J. S., Dunham, R. M., Bacho, R. A., Pastorino, E., & Portes, P. R. (1995). Adolescent identity exploration: A test of Erikson’s theory of transitional crisis. Adolescence, 30(120), 785-793.

Books in Dalton State College Library:

Sheehy, N. (2004). Fifty key thinkers in psychology. New York, NY: Routledge.

Videos and Tutorials:

Khan Academy. (n.d.) Erikson’s psychosocial development. Retrieved from

https://www.khanacademy.org/test-prep/mcat/individuals-and-society/self-identity/v/eriksons-psychosocial-development