Chapter 1 Money: Historical background and its Evolution into Today’s Economies

Learning Objectives

- Analyze the Evolution of Money

- Evaluate the Limitations of Barter Systems

- Differentiate Between Fiat and Non-Fiat Currencies

- Assess the Impact of Paper Money Introduction

- Trace the Advancements in Credit Systems

Pre-Monetary Economies: The Age of Barter

Before the invention of money, humans engaged in barter to facilitate the exchange of goods and services. Bartering involved the direct trade of items, which worked well in small, simple societies where people could easily find others with complementary needs. However, barter had several limitations. One of the most significant was the “double coincidence of wants”—both parties had to want what the other offered. Barter was inefficient for large-scale economies and diverse marketplaces, necessitating the development of a more practical medium of exchange.

Mesopotamian Barter Systems (3000 BCE): Early forms of trade occurred in the Fertile Crescent, where farmers traded surplus crops for tools, livestock, or other necessities.

Evolutionary First – Money as a Currency Commodity

To overcome the limitations of barter, societies began using commodities with intrinsic value as a medium of exchange. These commodities often held value in themselves (such as food, livestock, or precious metals) and were used to facilitate trade.

- Cattle and Livestock (Neolithic Age): In many early societies, livestock such as cows or sheep were used as a form of wealth and a medium of exchange.

- Grains of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia: Grain storage was controlled by state authorities, who used it as a medium of exchange and as payment for labor, particularly in state-driven projects such as pyramid construction.

- Shells & Cowries in Africa and Asia: Shells, particularly cowrie shells, were used extensively in trade in regions of Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands. Cowrie shells were traded for goods and services throughout Africa, Asia, Europe, and Oceania, and used as money as early as the 14th century on Africa’s western coast. Because the shells were small, portable, and durable, they served as excellent currency and were almost impossible to counterfeit, appearing in standard weights. King Gezo of Dahomey, now modern Benin, said he preferred cowries to gold for this reason, he would always receive a fair price.

Commodities as currency had some disadvantages, such as difficulty in transporting large quantities, perishability, or inconsistencies in value, leading to the rise of metallic money.

The Introduction of Metal Money – 2nd Evolution:

As civilizations grew more complex, the use of precious metals like gold, silver, and copper became widespread. These metals had intrinsic value due to their scarcity and usefulness in crafting jewelry and tools. They were durable, easy to transport, and could be measured accurately by weight. Thus, they became a preferred medium of exchange.

Early Metal Money:

Mesopotamia and Egypt (2500–2000 BCE): Silver bars were used as a form of payment. In Egypt, copper ingots were standardized for trade. Ancient Egyptians used copper ingots as a form of currency, often referred to as “oxhide ingots” due to their shape resembling an ox hide, where the metal was weighed and valued based on its weight rather than a standardized coin system; this practice was common in the Mediterranean region during the Late Bronze Age, before the introduction of coins.

Lydia (600 BCE): The Kingdom of Lydia, in modern-day Turkey, is often credited with the invention of the first true coins. These coins were made of electrum, a natural alloy of gold and silver, and stamped with symbols to certify their authenticity.

The Rise of Coinage: From the Greeks to the Romans

Coins revolutionized trade by providing a standardized and widely accepted form of money. They were small, durable, and easy to carry, making them ideal for trade across vast distances. Coins were minted by governments or city-states, often bearing the likeness of rulers or deities as a symbol of legitimacy.

Notable Developments in Coinage:

- Greek Coinage (5th Century BCE): The Greek city-states minted a wide variety of coins, which were used throughout the Mediterranean. Coins from Athens, such as the silver drachma, became particularly influential.

- Roman Coinage (3rd Century BCE – 5th Century CE): Rome developed a highly organized monetary system with coins made of gold (aureus), silver (denarius), and bronze (as). Roman coins were used throughout the vast Roman Empire, facilitating trade and taxation.

Coins not only served as money but also as a means for governments to disseminate propaganda, showcasing the power and wealth of rulers through imagery and inscriptions.

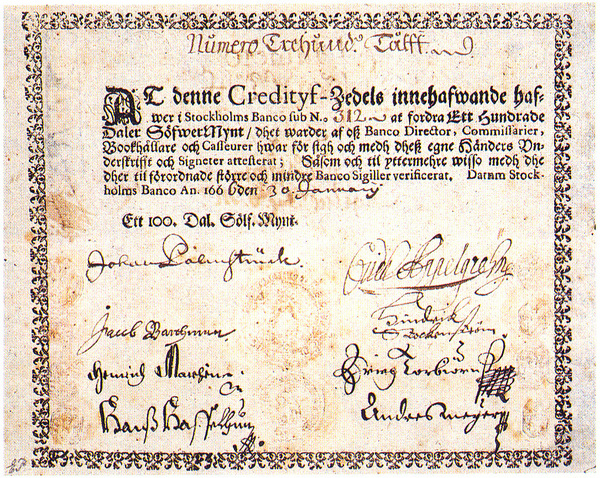

The Introduction of Paper Money – 3rd. Evolution

The next major innovation in the history of money came with the introduction of paper money. This development occurred in China during the Tang and Song dynasties. Initially, merchants would use promissory notes as a way to transfer large sums without carrying bulky coins. Over time, the state formalized this system.

Paper Money in China:

- Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE): The use of “feiquan” (flying cash) began as a form of promissory note in the Tang Dynasty.

- Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE): By the 11th century, the Song Dynasty had formalized the use of paper money (jiaozi). This system became widely adopted due to the increased volume of trade and the scarcity of metals like copper.

Paper money spread to the Middle East and Europe through trade, though it did not become fully institutionalized in Europe until centuries later.

Hints of a Future Banking System – 4th. Evolution

Queen Zanobia and The Romans

Queen Zenobia, the ruler of the Palmyrene Empire in the 3rd century CE, is renowned for her strategic leadership and ambition to expand her empire. Under her reign, Palmyra became a significant trade hub, connecting the Roman and Persian empires through its control of key trade routes.

To manage the empire’s growing economic power, Zenobia established a central money depository. This institution streamlined financial administration, facilitated trade, and ensured the efficient collection of taxes. The depository likely served as a secure location for storing precious metals and minted coins, which were essential for maintaining Palmyra’s vibrant economy and funding military campaigns.

Zenobia’s financial innovations contributed to the prosperity of her empire. However, her ambition ultimately led to conflict with the Roman Empire, culminating in her defeat and the annexation of Palmyra. Despite this, her financial policies remain a testament to her visionary governance.

The Crusades

The Crusades (1096–1291) played a pivotal role in the evolution of medieval European banking systems. As large numbers of European knights, pilgrims, and merchants traveled to the Holy Land, logistical challenges arose, including the safe transport of wealth over long and dangerous routes. These challenges spurred innovations in financial practices, laying the groundwork for modern banking.

One key development was the use of letters of credit. Pilgrims could deposit money with a financial agent or religious order, such as the Knights Templar, in Europe and receive a letter of credit. This document could then be presented at a Templar stronghold in the Holy Land, where funds would be disbursed. This system allowed travelers to avoid carrying large sums of cash, reducing the risk of theft.

The Templars, in particular, became central figures in early banking. Their widespread network of castles and monasteries served as secure repositories for wealth. They also offered services like loans, currency exchange, and financial mediation between European monarchs and the Crusader states.

Additionally, the financial demands of the Crusades—funding armies, constructing fortifications, and supplying provisions—encouraged the pooling of resources and the development of large-scale credit systems. These mechanisms laid the foundation for more formalized banking institutions that would emerge in the later Middle Ages.

In conclusion, the Crusades catalyzed the creation of a rudimentary banking system, combining innovative financial practices with the infrastructure of religious and military orders. These developments not only facilitated the Crusaders’ missions but also had lasting impacts on European economic systems.

Venetian Bankers

Venetian bankers played a crucial role in the development of modern banking practices during the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. As Venice emerged as a powerful maritime and trade hub, its economy required sophisticated financial systems to support commerce, investment, and governance. Venetian innovations in banking laid the groundwork for many elements of the modern financial system.

One key contribution was the establishment of deposit banking. Venetian banks allowed merchants to deposit their funds securely and provided written receipts, which could be used as a form of transferable credit. This practice facilitated trade by reducing the need for merchants to carry large amounts of coin, thus increasing security and efficiency.

Venetians also pioneered the use of bills of exchange. These instruments allowed merchants to transfer funds across distances without the physical movement of money, simplifying international trade and minimizing the risks associated with long-distance commerce. The bills served as an early form of modern checks and promissory notes. Additionally, Venetian bankers were instrumental in developing double-entry bookkeeping, a system that ensured accurate financial records by tracking debits and credits. This innovation not only enhanced financial transparency but also set the standard for modern accounting practices.

Venice’s government contributed to financial stability by establishing the Banco della Piazza di Rialto in 1587, one of the earliest public banks. It provided a regulated and trustworthy banking environment, offering services such as money transfers and currency exchange, which further supported Venice’s commercial dominance. These innovations facilitated the growth of international trade and laid the foundation for the sophisticated global financial systems we rely on today.

The Bank of England

The Bank of England, established in 1694, profoundly influenced the development of modern banking systems and regulatory frameworks. Created initially to finance England’s war efforts, it evolved into a model central bank and became a cornerstone of the global financial system.

One of its key contributions was the introduction of centralized monetary policy. The Bank of England became responsible for issuing standardized banknotes, replacing a fragmented system of private bank-issued currency. This innovation fostered trust in paper money and laid the groundwork for national monetary stability. The Bank also pioneered the concept of lender of last resort. During financial crises, it provided liquidity to struggling banks, preventing widespread banking collapses. This principle remains fundamental to central banking, ensuring systemic stability during economic downturns.

Another major development was the establishment of government debt management. The Bank facilitated the issuance of government bonds, enabling the state to raise funds efficiently. This practice helped create a liquid market for sovereign debt, an essential feature of modern financial markets. The Bank of England’s introduction of reserve requirements and prudential supervision further strengthened the banking system. By requiring commercial banks to hold a portion of their assets as reserves, it reduced the risk of over-leveraging and financial instability. Over time, these measures influenced the regulatory frameworks adopted by other central banks worldwide.

The Emergence of Modern Banking and Fiat Money – 5th Evolution

As trade expanded during the Renaissance and the early modern period, banking institutions began to emerge to facilitate the management of money. Merchants and governments increasingly used banks to store and transfer wealth, issue loans, and finance trade expeditions. The establishment of central banks was key to the control and stabilization of national currencies.

Key Developments:

- Banknotes and Bills of Exchange (16th–18th Century): In Europe, banks such as the Bank of Amsterdam issued notes that could be exchanged for precious metals. These notes were a precursor to modern banknotes.

- The Bank of England (1694): The creation of the Bank of England marked a pivotal moment in the history of banking and monetary policy. It began issuing banknotes backed by the British government.

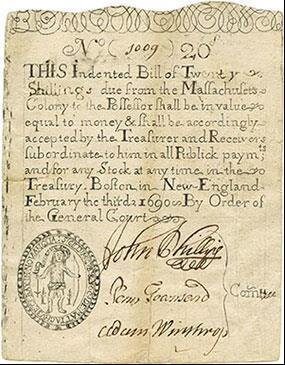

- Early US Paper Money:

Piece of paper money, from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, dated February 3, 1690. A short history of the USD and a Reflection on the Current World Order. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

-

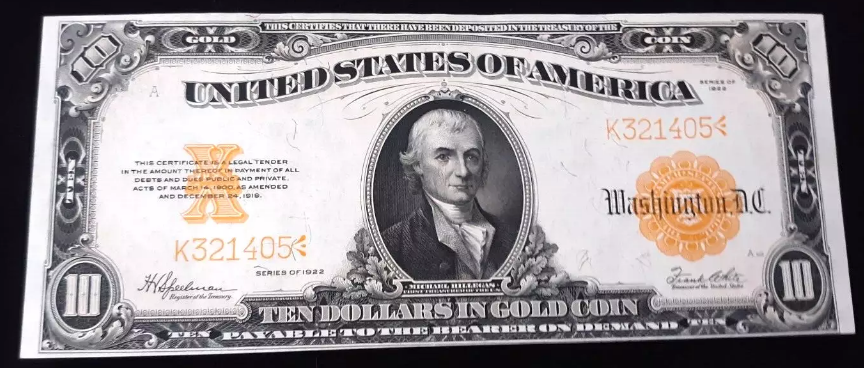

- Fiat Currency Characteristics: Fiat money is a type of government issued currency (in the US it is centrally controlled by the US Federal Reserve Bank) that is not backed by a precious metal, such as gold or silver, nor by any other tangible asset or commodity. In all countries around the world, just like the US, their fiat currency is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender and is authorized by certain government regulation. Most countries, use physical gold reserves, or other economic assets such as oil, to build the public “trust” for the designated value of their currency. The US, since the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, officially removed the “trust” with Gold, from its currency. Many countries since have followed suite.

Fiat money generally does not have intrinsic value. Value in this regard is present when used as a unit of account – or, in the case of currency, a medium of exchange – as in agreement between buyer and seller on its value. The issuing governments trust that it will be accepted by merchants and other people as a means of payment for goods and services. Fiat money is an alternative to commodity money, which is a currency that has intrinsic value because it contains, for example, a precious metal such as gold or silver which is embedded in it (a Gold Coin for example). Fiat also differs from representative money, which is money that has intrinsic value because it is backed by and can be converted into a precious metal or another commodity. Fiat money can look similar to representative money (such as paper bills), but the former has no backing, while the latter represents a claim on a commodity (which can be redeemed to a greater or lesser extent).

By the 20th century, most countries had transitioned to fiat money, meaning currency that has value because the government declares it to be legal tender, rather than being backed by a physical commodity like gold. The shift to fiat currency allowed governments greater flexibility in controlling the money supply.

In the financial world, currencies are classified as either fiat or non-fiat, with significant differences in their origins, values, and uses. Understanding these two types is crucial for grasping modern financial systems and the emerging digital currency landscape.

Key Characteristics of Fiat Currency:

- Government Issued: Fiat currencies are created and regulated by governments and central banks.

- Not Backed by Physical Commodities: Unlike earlier systems where money was backed by gold (the gold standard), fiat money derives value from the trust in and stability of the issuing government.

- Legal Tender: Fiat currency is legally accepted for transactions, meaning people are legally obliged to accept it in exchange for goods and services.

- Unlimited Supply: Governments and central banks can produce more fiat money as needed, which can lead to inflation if oversupplied.

- Value through Demand: The value of fiat currency is driven by demand within an economy, along with government stability and monetary policy.

Examples of Fiat Currencies:

- U.S. Dollar (USD)

- Euro (EUR)

- British Pound (GBP)

- Japanese Yen (JPY)

- Indian Rupee (INR)

Pros and Cons of Fiat Currency:

|

Pros |

Cons |

|---|---|

|

Governments can control money supply to combat inflation or stimulate the economy.

|

Vulnerable to inflation if excessive money is printed.

|

|

Facilitates easy exchange, payment, and standardized trade in economies.

|

Can suffer from devaluation if the public loses trust in the government |

|

Does not rely on physical commodities, avoiding the need for a large reserve of valuable assets.

|

Requires prudent economic management to maintain stability |

Table Pros and Cons of Fiat Currency

Picture of a 1 Trillion Zimbabwe Dollars

Non-Fiat Currency: Non-fiat currency refers to any form of currency that is not government-issued or does not have legal tender status within a particular jurisdiction. Non-fiat currencies may derive their value from physical assets, scarcity, or other mechanisms, and include types like commodity-backed currencies and cryptocurrencies.

Types of Non-Fiat Currency:

Commodity-Backed Currencies: These currencies have intrinsic value due to the backing of physical assets, such as gold or silver. In the past, the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold, a system known as the “gold standard.”

Cryptocurrencies

These are digital currencies that operate on blockchain technology, a decentralized system that does not rely on any central authority. Cryptocurrencies are often designed with limited supplies to combat inflation and derive value from factors like scarcity and demand.

Types / Brands of Crypto Currencies

- BitCoin – USA

- Ethereum

- Tether

- Bnb

- SOL

- Dogecoin

- Usdc

- Ton

- Xrp

- Cardano

- Plus, nearly 100 others listed on Wikipedia.

Generated image of a bitcoin token (Public Domain)

Characteristics of Crypto Currencies

- Decentralized: By definition all Cryptocurrencies are Decentralized. Cryptocurrencies are not controlled by a central authority, unlike fiat currencies.

- Secured by an algorithm: Bitcoin being the first introduced cryptocurrency used the Blockchain technology, several other Crypto’s also use Blockchain, however, newer and faster security algorithms are being developed. Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-based crypto.

- Immutability: Transactions on a blockchain are irreversible and cannot be changed or negated (claiming you didn’t start the transaction)

- Permissionless: Cryptocurrencies are a permissionless system. There is no Authority that controls who gets access to the network.

- Faster settlement: Cryptocurrencies can settle transactions quickly, even across borders and currencies. Fiat-based transactions can take 3 or more days to fully settle with the merchant. Crypto-based transaction settlement occurs in a sub-second time frame.

- Transparent: Cryptocurrencies have transparent ledgers.

- Predictable monetary policy: Cryptocurrencies have a predictable monetary policy that is controlled by the protocol, not by central banks

- Other Non-Fiat Systems: Systems like bartering, precious metals, or even local community-based currencies can serve as non-fiat forms of exchange, though they are less common in today’s globalized economy.

Characteristics of Non-Fiat Currencies

- Intrinsic or Speculative Value: Some non-fiat currencies, like gold-backed ones, have intrinsic value because they’re tied to physical assets. Cryptocurrencies, meanwhile, have speculative value based on perceived utility and adoption.

- Decentralization: Cryptocurrencies are typically decentralized, meaning they are not issued or regulated by any central bank or government.

- Limited Supply: Many non-fiat currencies, particularly cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, have a limited supply, which can make them inflation resistant.

- Alternative to Legal Tender: They may not be accepted universally for payments but are often used as investments or in specific economies or communities.

- Examples of Non-Fiat Currencies:

- Precious and Commodity Metals: Include Gold, Silver, Platinum, Palladium, Copper and many others. They are held and traded as a store of value and often considered a hedge against inflation.

- Bitcoin: A decentralized digital currency with a fixed supply of 21 million coins.

- Ethereum: Another digital currency that runs on its blockchain and has a wide range of applications in decentralized finance…..

- ….and many more

Pros and Cons of Non-Fiat Currency

Pros

- Non-fiat assets like gold or Bitcoin may retain value better in times of fiat currency devaluation or inflation.

- Cryptocurrencies offer transparency and decentralization, allowing users to transact without intermediaries.

- Limited supply of some non-fiat currencies can provide a hedge against inflation.

Cons

- Limited acceptance in general commerce, making it harder to use for everyday transactions.

- High volatility in cryptocurrencies makes them risky for short-term holdings.

- Lack of regulatory oversight in decentralized currencies can lead to security and fraud concerns.

How Non-Fiat Currency Works

The value of non-fiat currencies can be influenced by supply and demand, utility, and public perception. For commodity-backed currencies, value corresponds to the underlying asset. In the case of cryptocurrencies, value derives from market demand, utility, and the underlying technology (e.g., blockchain).

Fiat vs. Non-Fiat Currency: A Comparative Summary

|

Feature |

Fiat Currency |

Non-Fiat Currency |

|---|---|---|

|

Issuance |

Government or central bank |

Decentralized or commodity-backed |

|

Backing |

Government decree |

Commodity (gold/silver) or decentralized |

|

Value Determinants |

Trust in government, economy |

Scarcity, utility, market demand |

|

Supply Control |

Unlimited (can lead to inflation) |

Often limited (e.g., Bitcoin) |

|

Legal Tender |

Yes, in the issuing country |

No, limited acceptance |

|

Stability |

Generally stable, with inflation risk |

High volatility (cryptos) or commodity fluctuation |

|

Examples |

USD, EUR, GBP |

Gold, Bitcoin, Ethereum |

What Is Fungibility

Fungibility is the ability of a good or asset to be interchanged with other individual goods or assets of the same type. Fungible assets simplify the exchange and trade processes because fungibility implies equal value between the assets.

Understanding Fungibility

Fungibility implies that two things are identical in specification. Individual units can be mutually substituted. Specific grades of commodities such as No. 2 yellow corn are fungible because it does not matter where the corn was grown. All corn that’s designated as No. 2 yellow corn is worth the same amount. Commodities, common shares, options, and dollar bills are all examples of fungible goods.

Cross-listed stocks, or the shares of stock listed on multiple exchanges, are still considered to be fungible. The shares represent the same ownership interest in a firm whether you purchased them on the New York Stock Exchange or the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Fungibility is commonly associated with finance, but it’s also found in other disciplines, such as quantum physics. Cryptocurrencies are generally considered to be fungible assets, but some are unique and not interchangeable. They’re non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

Fungible vs. non-fungible

Fungible assets are of like kind, which makes them interchangeable. Non-fungible assets, on the other hand, have something unique about them that means one cannot be replaced by another.

Money is another example of a fungible asset. It doesn’t matter to person A if they’re repaid with a different $50 bill if person A lends person B a $50 bill. It’s mutually substitutable. Person A can be repaid with two $20 bills and one $10 bill and still be satisfied because the total equals $50.

Conversely, it’s not acceptable for one person to borrow a car from another person and then return a different car, even if it is the same make and model as the original. This is an example of non-fungibility. Cars aren’t fungible with respect to ownership, although the gasoline that powers the cars is. Other examples of non-fungible assets are:

Diamonds: Individual diamonds have different cuts, colors, sizes, and grades, so they’re not interchangeable.

Baseball cards: Each card has unique qualities such as rarity that add or subtract from its value.

Real estate: Each house experiences different levels of noise and traffic, is in varying states of repair, and has unique views of surrounding areas, even on a street of identical houses.

Special Considerations

The line between fungibility and non-fungibility may be a thin one. Gold is generally considered to be fungible because one gold ounce is equivalent to another gold ounce. But when otherwise fungible goods are given serial numbers or other uniquely identifying marks, they may no longer be quite as fungible. Adding unique numbers to bars of gold, collectibles, and other items makes it possible to distinguish them, which makes them non-fungible.

For example, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York offers gold custody services to central banks and governments around the world by storing gold bars in its underground vault. All the gold bars deposited into the vault are weighed and inspected to confirm they match the depositor instructions. The exact bars deposited to the New York Fed are the exact ones returned upon withdrawal, so these types of gold deposits are not considered fungible.

What Is the Meaning of Fungible

Fungible means that an item, asset, or commodity can be replaced with something of like kind when fulfilling a contract or paying a debt. Interchangeable goods are fungible; unique goods are non-fungible.

Why Does Fungibility Matter

Fungible assets create a flow in trade and exchange processes because they’re essentially equal in value. This can be a factor in healthy economies. A decrease in value in one sector or country can be offset by a rise of a fungible asset in another.

What Is a Fungible Issue

A fungible issue is a bond that replicates one that’s been previously offered by the same company. Its terms are the same but the yield will most likely be different.

What Are Non-Fungible Tokens

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are assets that are not interchangeable. They’re often digital and can include assets such as music, images, and videos, as well as some forms of cryptocurrency. You can have a right to ownership if you purchase an NFT but this right doesn’t necessarily translate to outright ownership of the asset

Key Takeaways

-

Fungibility is the ability of a good or asset to be readily interchanged for another of like kind.

-

Goods and assets such as cars and houses that aren’t interchangeable are non-fungible.

-

Money is a prime example of a fungible asset because a $1 bill is easily convertible into four quarters or 10 dimes.

-

Unique items such as cars, houses, or artwork are non-fungible.

-

The line between fungibility and non-fungibility of some assets can be murky.

The Bottom Line

Fungible assets are identical. One can be substituted for another without fuss or penalty. Stock shares listed on multiple exchanges are an example of fungible assets because they provide the same ownership interest regardless of who purchases them or where they’re purchased. This strengthens the reliability of the asset in question, and it can be an important consideration for the average investor.

Non-fungible assets, on the other hand, are unique in some way, which means one cannot be replaced with the other. Houses, gemstones, and artwork are all non-fungible goods.

The Gold Standard of Money and its Abandonment

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many nations adopted the gold standard, a monetary system in which the value of a country’s currency was directly linked to a specific quantity of gold. This system provided stability and facilitated international trade but also limited governments’ ability to respond to economic crises.

Key Events

Gold Standard Era (1870–1914): The gold standard was used by most major economies, promoting international stability in exchange rates.

World Wars and the Great Depression: The economic strains of World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II made it increasingly difficult for nations to maintain the gold standard.

Bretton Woods System (1944–1971): After World War II, the Bretton Woods Agreement established a modified gold standard, with the U.S. dollar pegged to gold and other currencies pegged to the dollar. This system collapsed in 1971 when President Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold, marking the end of the gold standard.

The Rise of “Plastic” Money – The History and Evolution of Credit Cards

Early Beginnings of Credit

The concept of buying goods and services on credit dates back thousands of years. In ancient civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Rome, traders and merchants used clay tablets, leather notes, and other forms of record-keeping to note credits and debts. In medieval Europe, the use of credit expanded with the rise of trade routes, and merchants developed systems of IOUs and promissory notes. These systems, however, relied heavily on trust and had limited reach beyond local or trusted connections.

With the advent of banks in Renaissance Italy and later in England, financial institutions began issuing formalized credit. Wealthy individuals and merchants could secure loans or lines of credit based on their reputation, assets, and collateral. However, the idea of extending credit for daily consumer purchases was still in its infancy.

The Birth of Charge Accounts and Credit Tokens (1800s-1940s)

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, department stores, oil companies, and other businesses began issuing credit accounts or “charge accounts” to encourage loyalty among customers. These accounts allowed customers to make purchases without immediate payment, and instead pay the amount owed at a later date, usually within a monthly billing cycle.

Charge Plates and Charge Coins/Tokens

By the early 1900s, some businesses issued metal coins or plates, which were small, coin-like objects made from metal or celluloid with unique identifying numbers for each customer. These items, known as “charge coins” or “charge plates,” functioned as early versions of store-specific credit cards. The department store would keep a record of purchases made by the customer using the coin or plate, which allowed for easier tracking and improved security.

Oil Company Credit Cards

During the 1920s and 1930s, as automobile ownership increased, oil companies began issuing their own credit cards to loyal customers. These early cards could only be used at the issuing company’s locations, making them limited in scope compared to today’s multi-use cards. The cards were primarily metal and were embossed with the cardholder’s name and account information, which could be imprinted on a sales slip.

These early credit systems, though foundational, were restrictive since each card was tied to a specific retailer or company. However, they laid the groundwork for the modern credit card system by fostering consumer reliance on credit for convenience and loyalty.

The First Universal Credit Card (1950s)

The 1950s marked the true beginning of the modern credit card. The first universal credit card – one that could be used at multiple locations rather than just one store or company – was introduced by the Diners Club in 1950.

The Diners Club Card (1950)

The story of the Diners Club card began when businessman Frank McNamara dined at a New York City restaurant but realized he had left his wallet at home. This inspired him to create a card that could be used to pay for meals and settled with a single monthly bill. In 1950, the Diners Club launched its card, which could initially be used at 27 participating restaurants. It was a charge card, meaning the balance had to be paid in full each month, and it was primarily aimed at business travelers.

Founded by Frank McNamara in 1950, the Diners Club card was one of the country’s earliest charge cards. Before the era of plastic credit cards or digital payments, the convenience of paying without carrying excessive cash was revolutionary. Members simply presented their Diners Club card, and at the end of the month, they received a bill for all their charges. Diners Club would then pay the restaurant, deducting a 5-7% processing fee.

In 1951, Alfred Bloomingdale’s charge card company, “Dine and Sign,” merged with Diners Club. Bloomingdale became a key figure in the company’s expansion. The Diners Club card’s success demonstrated that consumers valued the convenience of a multi-use charge card, paving the way for the development of other universal credit systems.

Bank-Issued Credit Cards (1950s-1970s)

While the Diners Club pioneered the idea of a universal charge card, the first true revolving credit card, where cardholders could carry a balance, was introduced by banks.

BankAmericard (1958): In 1958, Bank of America issued the first bank credit card, known as the BankAmericard, in Fresno, California. The card was unique because it allowed consumers to carry a balance and make monthly payments with interest, marking the introduction of revolving credit. This model greatly expanded the potential of credit cards by making it easier for consumers to purchase items without full repayment each month.

Master Charge (Now MasterCard) (1966): In response to Bank of America’s success with BankAmericard, a group of California banks formed the Interbank Card Association (ICA) in 1966, later rebranded as MasterCard. Like BankAmericard, Master Charge allowed revolving credit and offered a unified payment method for merchants, increasing competition in the emerging credit card market.

By the end of the 1960s, these two card networks had expanded nationwide, paving the way for a more integrated credit card infrastructure across the U.S. and internationally.

Technological Advancements and Magnetic Strips (1970s-1980s)

Technological innovation in the 1970s revolutionized the credit card industry by increasing card security and efficiency in processing.

Magnetic Stripe (1970s)

IBM pioneered the use of magnetic stripes on credit cards in the early 1970s. The magnetic stripe, embedded with account information, allowed credit card details to be read by electronic terminals, eliminating the need for manual imprinting. This greatly accelerated the speed and accuracy of credit card processing and reduced fraud.

Automated Teller Machines (ATMs)

The introduction of ATMs in the 1970s, which could accept credit cards for cash advances, further increased credit card accessibility. Customers could withdraw cash using credit cards at any time, expanding the convenience and functionality of the cards beyond just purchasing goods and services.

Electronic Authorization (1980s)

As technology advanced, electronic terminals became widespread, allowing merchants to receive instant authorization for transactions. This step reduced the risk of fraud and simplified the purchasing process, making credit card transactions faster and more secure.

The Growth of International Credit Card Networks (1980s-1990s)

The Growth of International Credit Card Networks (1980s-1990s)

During the 1980s and 1990s, credit card use became more common internationally, driven by the expansion of credit card networks like Visa (formerly BankAmericard) and MasterCard. The international presence of these networks allowed cardholders to use their cards in multiple countries, increasing the convenience of credit cards for travelers and boosting global commerce.

Visa and MasterCard Global Expansion: The Visa and MasterCard networks expanded their reach by partnering with banks in various countries, creating a seamless system for credit card transactions across borders. This move contributed to the rise of globalized banking, where consumers could use credit cards for purchases internationally, and merchants could accept a variety of cards.

Emergence of Credit Card Regulations: Governments began to implement regulations to protect consumers from unfair practices and high-interest rates. In the U.S., the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) and the Fair Credit Billing Act (FCBA) established rules for disclosure and billing error resolution, providing consumers with greater transparency and protection.

The Digital Era: Chip Technology and Contactless Payments (2000s-Present)

The new millennium brought about significant advancements in credit card technology, primarily aimed at enhancing security and convenience.

EMV Chip Technology: EMV (Europay, MasterCard, and Visa) chip technology was introduced in the 1990s and became widespread in the 2000s. The embedded microchip in each card made it more difficult for fraudsters to copy card information, significantly reducing counterfeit fraud. By 2015, the U.S. adopted EMV technology, spurring a shift from magnetic stripes to chip-enabled cards.

Contactless Payments: Contactless payments emerged in the 2010s, allowing cardholders to tap their cards on payment terminals to complete transactions. Contactless cards use near-field communication (NFC) technology, which enables faster transactions and enhanced security. Additionally, mobile payment platforms such as Apple Pay, Google Wallet, and Samsung Pay use similar technology, allowing users to store credit cards digitally and make payments via smartphones.

Virtual Cards and Online Shopping: The rise of e-commerce has further transformed the credit card landscape. Consumers now make millions of online purchases daily, and credit card companies have responded with virtual cards, which use temporary numbers for secure online transactions. Digital security features, including multi-factor authentication, tokenization, and encryption, are now commonplace in credit card systems to protect users’ sensitive information.

In 2014, the iPhone 6 became the first mobile phone to support on-line purchase and payment. Courtesy Apple, Inc.

The Digital Age and Cryptocurrency

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the rise of the internet and advances in technology gave rise to new forms of money, including digital currencies and cryptocurrencies.

Digital Money

Electronic Transfers and Credit Cards: In the latter half of the 20th century, credit cards, debit cards, and electronic fund transfers (EFTs) revolutionized how people managed and spent money. Digital banking allowed for real-time transfers and payments across borders.

Cryptocurrency (Bitcoin, 2009–Present): Bitcoin, introduced in 2009 by an anonymous individual or group using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, was the first decentralized cryptocurrency. Based on blockchain technology, Bitcoin allows for peer-to-peer transactions without the need for a central authority. Since then, numerous other cryptocurrencies have emerged, sparking debates over their potential to replace traditional currencies.

The Future of Money

As digital and decentralized forms of money continue to evolve, questions about the future of monetary systems are increasingly relevant. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), stablecoins, and cryptocurrencies are expected to play a significant role in shaping future financial ecosystems.

Feedback/Errata