Chapter 4: Power, Security, and Superheroes as WMDs

Captain America Said ‘Nah’ to the Sokovia Accords

4.3: Security Dilemmas and Arms Races

In international relations, states often engage in a delicate balancing act, trying to increase their own security without provoking suspicion or fear in other countries. This dynamic—where efforts to enhance security create unintended tensions—is known as the security dilemma and is a recurring theme in both history and modern politics, particularly around nuclear arms and military alliances. To understand why states sometimes end up in high-stakes confrontations despite intending to protect themselves, political scientists use concepts like the security dilemma, arms races, and deterrence. Each concept captures different aspects of how countries pursue security while managing external threats. Using the storyline of Captain America: Civil War, where the Avengers grapple with power, oversight, and security, we can explore how these pressures create challenges, even when all parties seek stability.

Conflicts often start with well-intentioned efforts. In Captain America: Civil War, the Sokovia Accords are introduced to bring oversight to the Avengers, aiming to control their impact on global security. Yet, the result is far more complicated. As in real-world politics, when one state takes steps to increase its security, other states often interpret these moves as potential threats. This reaction is central to the , where a state’s efforts to feel more secure inadvertently make other states feel less secure, leading to cycles of mistrust and escalation. Captain America’s opposition to the Accords reflects this concept: he fears that submitting to external oversight will weaken the Avengers’ ability to act freely in crises, effectively reducing their security. Iron Man, meanwhile, supports the Accords as a way to ensure global stability and transparency. This split mirrors the Cold War era, where the U.S. and Soviet Union each increased their military capabilities out of fear of the other’s strength, spiraling into mutual suspicion and tension. The security dilemma shows how the pursuit of security can backfire, creating division rather than peace.

provides another strategy for navigating these security challenges. It operates on the principle of using the threat of retaliation to prevent adversaries from acting aggressively, maintaining peace by making the costs of conflict unacceptably high. In Civil War, Iron Man’s support for the Sokovia Accords functions as a type of deterrence, where the Accords aim to establish clear consequences for any superhero actions taken outside government oversight. In real-world contexts, nuclear deterrence during the Cold War worked similarly: the U.S. and Soviet Union each knew that launching a nuclear attack would prompt catastrophic retaliation. This doctrine of “massive retaliation” helped keep an uneasy peace, as both sides recognized the devastating costs of conflict. Deterrence remains relevant today in global nuclear policy, where the threat of retaliation serves as a constant reminder that unchecked power can have disastrous consequences.

Once states feel threatened, they frequently respond by expanding their own military capabilities to match or outdo potential rivals. In Civil War, a similar dynamic unfolds as the Avengers split into two competing factions, each recruiting more members to their “side” fearing that they won’t win, escalating their resources and tactics in response to the perceived threat from the other side. This dynamic resembles an , where states engage in a competitive buildup of weapons or technology to avoid falling behind. Arms races are fueled by the fear that one side’s superior military capabilities could enable it to dominate others. For example, the Cold War saw the U.S. and Soviet Union competing to amass nuclear arsenals, each fearing that falling behind would expose them to domination. Unlike the Cold War though, In Civil War, the Avengers’ divisions lead to an increasingly destructive standoff will an eventual direct confrontation between the two sides. During the Cold War, the threat of mutually assured destruction kept the two sides from directly fighting one another.

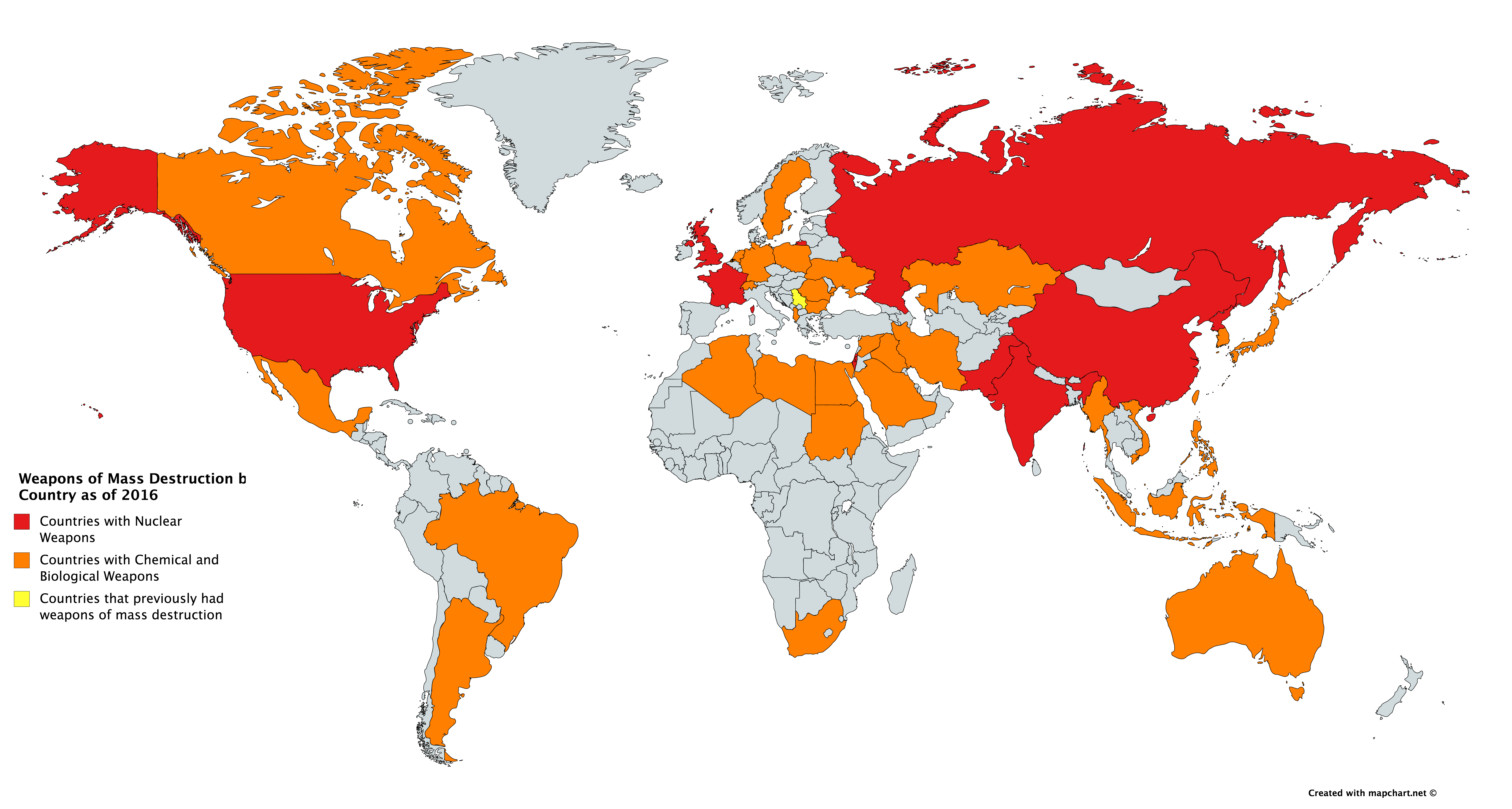

When the pursuit of security reaches its most intense and terrifying form, we arrive at the concept of , where both sides possess enough nuclear weapons to annihilate each other, effectively preventing war because of the catastrophic consequences. MAD emerged during the Cold War as a strategic doctrine grounded in deterrence theory, particularly within the Realist tradition of international relations. The logic is chillingly simple: if both superpowers—primarily the United States and the Soviet Union—had second-strike capabilities (the ability to retaliate even after being hit first), then initiating a nuclear war would be tantamount to national suicide. Ironically, this horrific balance of terror created a kind of stability; both sides refrained from direct conflict, knowing that any nuclear exchange would result in complete devastation on both ends. Think of it as the ultimate “you hit me, we both go down” scenario.

This strategy influenced not only military planning but also diplomatic behavior, arms control treaties, and public consciousness. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 brought the world dangerously close to testing MAD in practice, as both superpowers teetered on the edge of nuclear war before ultimately stepping back. In that moment, the sheer fear of mutual annihilation served as the final restraint. But MAD also had psychological effects—it created an atmosphere of constant dread, in which everyday citizens lived under the shadow of possible nuclear extinction. The doctrine made peace possible, but it was a peace forged through fear, not trust.

The enduring lesson of MAD is that the very tools created for security can produce their own kind of insecurity. The presence of such overwhelming destructive power meant that any miscalculation, misunderstanding, or rogue decision could trigger irreversible catastrophe. In this sense, MAD is not just a historical policy—it’s a vivid demonstration of a central dilemma in international relations: the security dilemma, where actions taken by one state to increase its own safety inadvertently threaten others, prompting an arms spiral. MAD simply pushes that dilemma to its apocalyptic extreme. Even today, as new nuclear states emerge and old rivalries simmer, the shadow of MAD reminds us that deterrence may prevent war—but at the cost of permanent existential risk.

In cases where deterrence is perceived to be failing, some states consider taking matters into their own hands. This is where the concept of a comes in—a military attack launched based on the belief that an enemy’s attack is imminent, aiming to neutralize the threat before it materializes. In Civil War, Captain America’s choice to act independently, often without waiting for government approval, resembles a preemptive strike: he believes that threats like Helmut Zemo require immediate action, regardless of bureaucratic constraints. In a real-world parallel, Israel’s 1967 Six-Day War illustrates the logic of a preemptive strike. Facing threats from neighboring countries that seemed on the verge of launching attacks, Israel struck first to secure a strategic advantage and reduce the risk of invasion. While preemptive strikes can provide immediate security, they are high-risk moves that often spark retaliation and heighten long-term instability, as the targeted state then feels justified in counterattacking. This escalation dynamic shows how preemptive strikes, meant to prevent conflict, can often intensify it instead.

Through these concepts—security dilemmas, arms races, deterrence, preemptive strikes, and mutual assured destruction—we gain a clearer understanding of how international conflicts often escalate, even when no side truly wants war. Captain America: Civil War brings these ideas to life, illustrating how efforts to manage power and security can easily turn into divisions that threaten the very stability they seek to preserve. By examining these dynamics, students of international relations can better understand why achieving lasting peace requires not just military strength but also diplomacy, trust, and, ideally, restraint. In a world where power and security are constantly in flux, the balance between protection and provocation remains as delicate as ever.

A situation where one state's efforts to increase its security make other states feel less secure, leading to an escalation of arms and mistrust.

A strategy where states use the threat of retaliation, particularly with nuclear weapons, to prevent an adversary from initiating conflict.

A competitive buildup of military capabilities between states, often driven by fear of falling behind rivals in terms of power.

A doctrine where both sides in a conflict possess enough nuclear weapons to destroy each other, thus deterring war due to the catastrophic consequences.

A military attack launched with the belief that an enemy is planning an imminent attack, aiming to neutralize the threat before it materializes.

Feedback/Errata