Chapter 3: The State in International Relations- Nationalism and State Power in Dystopian Futures

May the Odds Be Ever in Your State’s Favor

3.5: The Changing Nature of Statehood

In an increasingly interconnected world, the concept of statehood is evolving, with new entities and global forces challenging traditional definitions of sovereignty and independence. Traditionally, a state is defined as a territory with a permanent population, a functioning government, and international recognition. However, globalization, transnationalism, and the emergence of quasi-states and de facto states have blurred these lines, creating entities that operate outside of traditional norms. In The Hunger Games series, Panem’s districts represent fragmented regions within a larger, authoritarian state, illustrating how regions can develop their own identities and aspirations for autonomy even under central control. For example, District 13, long thought to have been destroyed, operates autonomously in secret, showing how political and cultural independence can emerge even without formal recognition. Today, the changing nature of statehood raises questions about sovereignty, autonomy, and recognition in a world where non-state actors and cross-border connections increasingly influence political power. Understanding these new forms of state-like entities and the impact of globalization on state sovereignty provides insight into the complexities of modern international relations and challenges us to rethink what it means to be a state in today’s world.

Not every territory that looks like a state earns a seat at the international table. represent entities that exhibit some characteristics of statehood, but not all. These entities often have a population that seeks independence or self-rule but lacks the international legitimacy to be recognized as a state. In Mockingjay – Part 1, District 13 operates much like a quasi-state: it has a government, population, and defined territory underground, but the Capitol denies its existence and legitimacy, portraying it as a myth to maintain control over the districts. Despite lacking formal recognition, District 13 acts as an independent region, with its own governance structures, military operations, and leadership under President Coin, who strategically supports the rebellion. Real-world quasi-states, such as Palestine, similarly face challenges in gaining full recognition, as they have some state-like characteristics but struggle to achieve full sovereignty due to political complexities and opposition from more powerful states. Quasi-states highlight the tension between state functions and recognition, as they often operate independently despite lacking full international legitimacy. This blurred line between independence and recognition underscores the challenges of defining statehood in a complex global system.

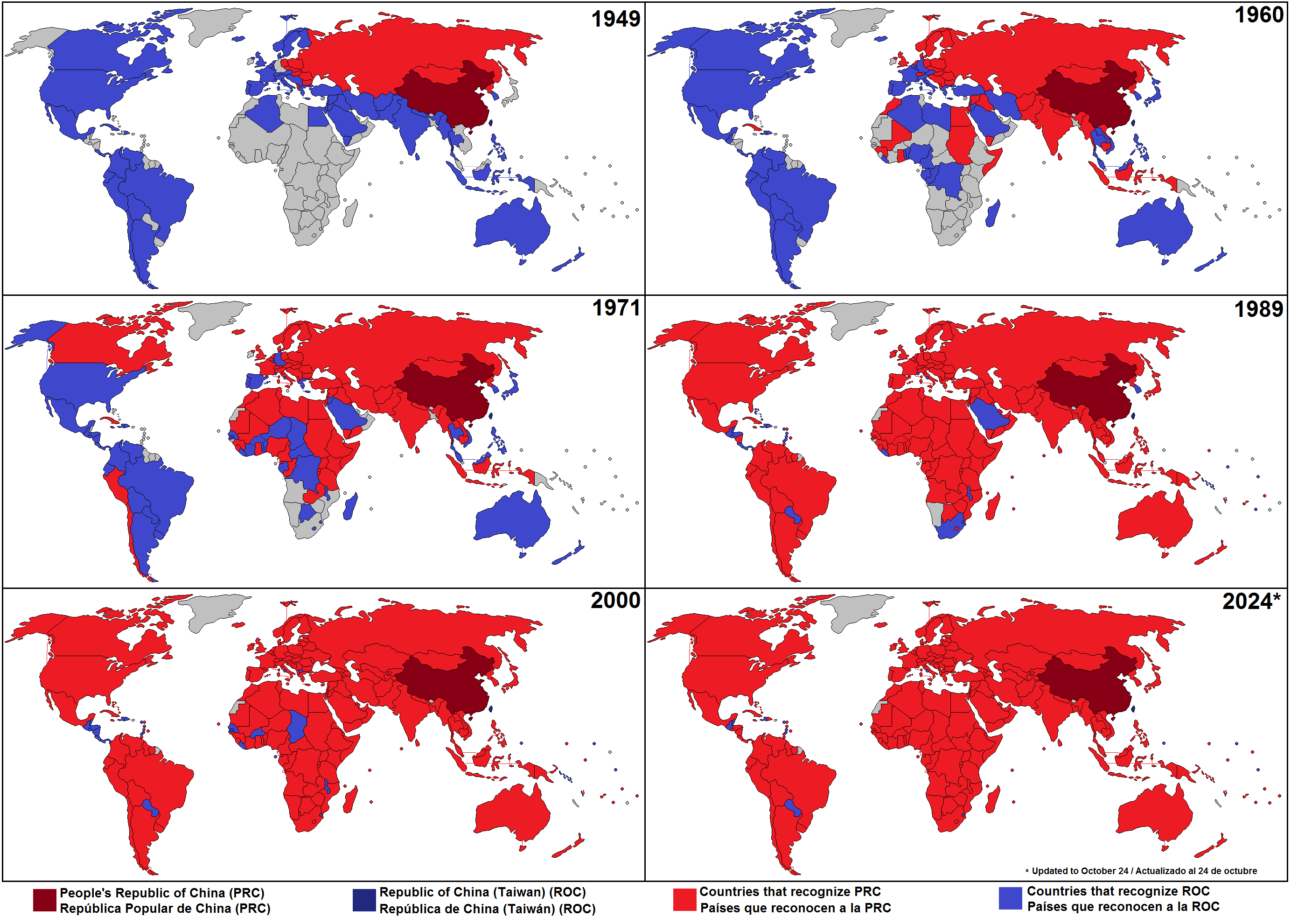

Sometimes, a state can function perfectly well while the rest of the world pretends it doesn’t exist. A takes quasi-statehood a step further, functioning fully as an independent state but lacking official recognition from the global community. De facto states may have complete control over their territories, economies, and political systems, yet they remain unrecognized by many countries or international organizations. Taiwan is a prominent example, as it operates independently with its own government, economy, and military, but is not widely recognized as a sovereign state due to diplomatic pressures from China. In The Hunger Games, if the rebellion succeeds in toppling the Capitol, the districts could resemble a de facto state in the transitional period, functioning independently yet awaiting formal recognition as they reorganize and redefine their governance structures. This transitional stage is apparent when District 13 begins coordinating military efforts and providing leadership, but its legitimacy remains unclear to the other districts. De facto states challenge traditional ideas of statehood by asserting independence and governance, even when denied full legitimacy on the international stage. These entities reveal how sovereignty can exist in practice even when it is not officially recognized, complicating the international system’s ability to define what qualifies as a state.

In the modern era, has become one of the most powerful forces shaping the international system. It refers to the increasing interconnectedness of countries through trade, communication, technology, finance, and cultural exchange. As goods, ideas, and people move more easily across borders, the traditional boundaries of state authority are being challenged. Economically, globalization allows countries to access larger markets and benefit from international investment, but it also makes them vulnerable to global supply chain disruptions and the influence of powerful multinational corporations. For example, a smartphone assembled in China may include parts manufactured in South Korea, designed in the United States, and sold in markets around the world—no single state controls the entire process, yet all are economically tied to it. Culturally, globalization can lead to rich exchanges of ideas, language, fashion, and entertainment—but it can also prompt concerns about cultural homogenization. The global popularity of American fast-food chains, pop music, and streaming platforms, for instance, has influenced lifestyles and consumer habits in places as diverse as Egypt, Brazil, and Indonesia. While many celebrate this cultural blending, others worry about the erosion of local traditions and languages. These global flows of culture and commerce can limit a state’s ability to shape its own identity and economy on its own terms. As a result, globalization presents a fundamental tension in international relations: how can states preserve sovereignty and self-determination while participating in a world that increasingly transcends borders? This growing web of global ties has also given rise to transnationalism—a system of social, economic, and political networks that operate across national boundaries, often connecting people and organizations more directly than states themselves.

Ideas, like wildfire, don’t stop at borders—they spread. complicates statehood further by creating interconnections that cross borders, involving both state and non-state actors in ways that reshape sovereignty. Transnationalism allows ideas, capital, people, and goods to move across borders, forming networks that are often independent of individual governments. In The Hunger Games, the Capitol’s control begins to weaken as people across districts communicate and unify, effectively forming a transnational resistance. This shift is particularly evident in the spread of Katniss Everdeen’s symbolic role as the Mockingjay, which transcends individual district loyalties and inspires collective resistance against the Capitol’s authority. Much like how modern social movements—such as climate activism or human rights campaigns—spread across borders and create global pressure for change, the districts’ shared cause becomes larger than any one territory. Real-world examples of transnationalism include environmental organizations like Greenpeace or human rights movements such as Amnesty International, which challenge traditional state control over domestic issues by creating global networks of influence. As transnational networks grow, they alter the relationship between states and their populations, making it increasingly difficult for governments to enforce sovereignty in an interconnected world. This erosion of control highlights how transnationalism reshapes power dynamics on both a domestic and international level.

As we explore quasi-states, de facto states, transnationalism, and globalization, it becomes clear that traditional concepts of statehood and sovereignty are evolving. Statehood isn’t what it used to be—now the lines are blurrier than ever. These modern forces blur the lines between state and non-state actors, creating new forms of political organization and interdependence that reshape the international system. In The Hunger Games, the districts’ push for autonomy, the influence of District 13, and the rise of cross-district solidarity offer a fictional but striking example of how state-like entities emerge and challenge centralized power. By examining how these concepts play out both in real life and in fictional settings, we gain a deeper understanding of the complexities and challenges facing statehood in a globalized world. This exploration invites us to think critically about how sovereignty, independence, and cooperation are defined and negotiated in an ever-changing international landscape.

An entity that lacks full sovereignty or recognition but has some characteristics of statehood, such as territorial control or a population seeking independence.

A region or entity that operates as an independent state without official recognition by the international community (e.g., Taiwan).

The increasing interconnectedness of economies, societies, and cultures across the globe.

The increasing interaction and interdependence between states and non-state actors across borders, which can challenge the traditional notion of state sovereignty.

Feedback/Errata

1 Response to Chapter 3: The State in International Relations- Nationalism and State Power in Dystopian Futures